After printing technology spread 358 different editions were produced, with an assumed print run of around 1000 copies each, therefore representing an estimate of 350,000 books circulating around Europe between 1472 and 1650. The collaborative project "De Sphaera. Knowledge System Evolution and the Shared Scientific Identity of Europe," developed with the MPIWG’s Research IT team and the Berlin Center for Machine Learning, utilizes this exciting collection to investigate processes of the evolution of knowledge.

The analysis of the corpus shows that knowledge was gradually being reshaped from a material and technical perspective. The readers were increasingly requested to learn how to build their own armillary sphere in order to better understand Sacrobosco’s orginal text, which was a qualitative introduction to geocentric cosmology. From Mauro da Firenze, Johannes de Sacrobosco, Annotationi sopra la lettione della spera del Sacro Bosco. Dove si dichiarano tutti e principii Mathematici et Naturali, che in quelle si possan desiderare. Firenze: Lorenzo Torrentino, 1550, 96 (hdl.handle.net/21.11103/sphaera.101035).

Our repository—CorpusTracer—was developed specifically for studies in cultural heritage and hosts a wide range of heterogeneous and highly-interconnected data. The De Sphaera project aims at establishing new approaches in the frame of computational history, combining individual historical exploration of the sources with interdisciplinary investigations involving digital humanities and data science, mathematics of complex systems, and machine learning.

The home screen of CorpusTracer, featuring a search field and recently edited book and person record, with images and biographical data of persons are drawn from Wikidata.

The Structured Search interface implemented in CorpusTracer allows also non-expert users to formulate complex query on the graph database.

The digitized pages of each book are accessible through a IIIF compatible image viewer, which enables close-up inspection of the images as well as identification and annotation of elements on the page, such as illustrations.

Detailed bibliographic data have been captured about all the editions and can be accessed through the database interface.

Epistemic Communities

Since 2017, De Sphaera has used two different approaches to explore the emergence and consolidation of communities in early modern Europe—both social and epistemic—spanning around 200 years. First, a Working Group entitled The Authors of the Commentaries investigated the profiles and motives of early modern commentators of scientific textbooks. Second, the wealth of data collected from the sources—data extracted from scientific texts, images and tables—allowed for a data-driven analysis that revealed an establishment of epistemic communities during the sixteenth century that promptly shaped scientific knowledge across the continent.

Geotemporal distribution of the production of the treatises belonging to the corpus. Visualization produced using Palladio. Source: F. Kräutli.

What could be ascertained from this? As demonstrated in the open-access Working-Group volume, De sphaera of Johannes de Sacrobosco in the Early Modern Period: The Authors of the Commentaries (Springer Nature, 2020), the authors of scientific commentaries on textbooks were all, without exception, deeply involved in university life. Their commentaries mirror the expansion of the late Medieval knowledge system—mainly characterized by the interrelation between cosmology, astrology, astronomy, and medicine, into the realm of geography, cosmography, and nautical astronomy—dictated by the growing integration of mathematical work across all of the disciplines.

The diffusion of print technology first amplified and spread Medieval knowledge: out of 208 authors identified in the corpus, a mere 58 were alive when the editions containing their texts were published. Only slowly did printers and publishers begin producing more contemporary scientific texts. Potential cross-relationships, based on more than one author being alive whose texts were printed in the same book, involve only 18.

CorpusTracer uses a graph-based data model based on Linked Data and the CIDOC-CRM ontology. This graphical representation depicts which entities are present in the database (books, persons, text parts, languages, etc.) and the relationship between them.

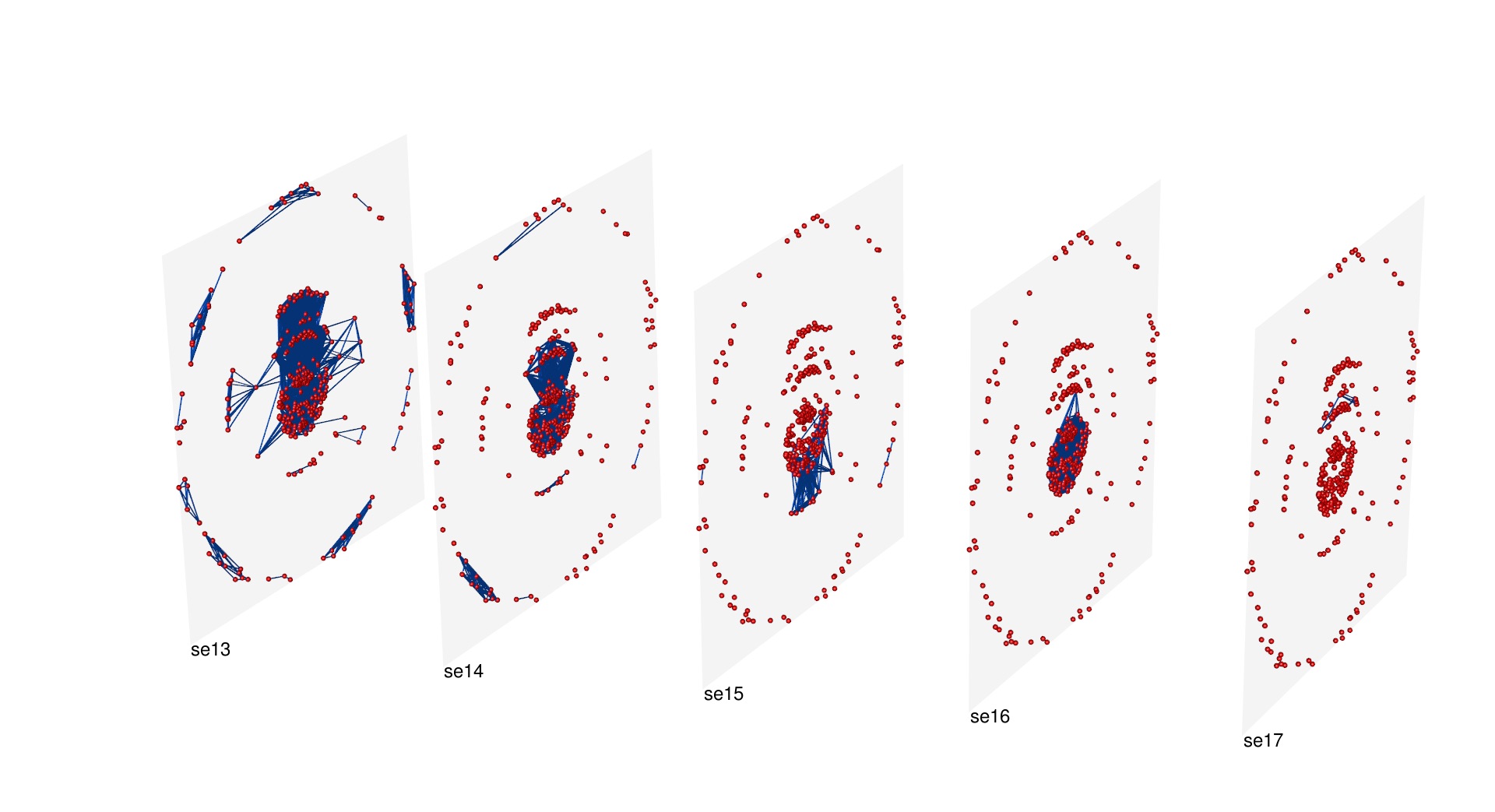

The data extracted from the De sphaera sources are intended to mirror the mechanisms of the production of scientific knowledge. The treatises were dissembled into what we define “knowledge atoms.” These are identified by portions of text (“text parts”) and their reoccurrences throughout the corpus over time. By determining these portions as “original texts,” “para-texts,” “commentaries,” “translations,” “text fragments,” and all possible combinations of these, the data were modeled as a multiplex network of five layers. These were then analyzed in collaboration with the research unit Nonlinear Dynamics and Time Series Analysis, headed by Holger Kantz at the Max Planck Institute for the Physics of the Complex Systems, and the results published open-access as “The Emergence of Epistemic Communities in the Sphaera Corpus: Mechanisms of Knowledge Evolution” (Journal of Historical Network Research, 2019). Analysis of the data shows how Wittenberg printers, active in the framework of the Protestant Reformation were able to take the lead in orienting the content and format of textbooks in astronomy across Europe.

Visualization of the multi-layer network by means of muxViz (muxviz.net). Ref: https://academic.oup.com/comnet/article/3/2/159/376726

Next Steps: Printers and Actors

The role of printers, publishers, and booksellers in shaping scientific endeavor in the early modern period is proving to be absolutely decisive, therefore steering the De Sphaera research in this direction. A new Working Group—The Printing Press and the European Academic Milieu 1470–1650: Defining Modes of Interaction and Scientific Exchange in the World of Printed Words—seeks to investigate the economic and institutional mechanisms of the academic book market during the early modern period. A first meeting of 18 international scholars in early modern university and book history, organized by Matteo Valleriani and Andrea Ottone from the project The Early Modern Book Trade headed by Angela Nuovo, will take place at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in early 2020.

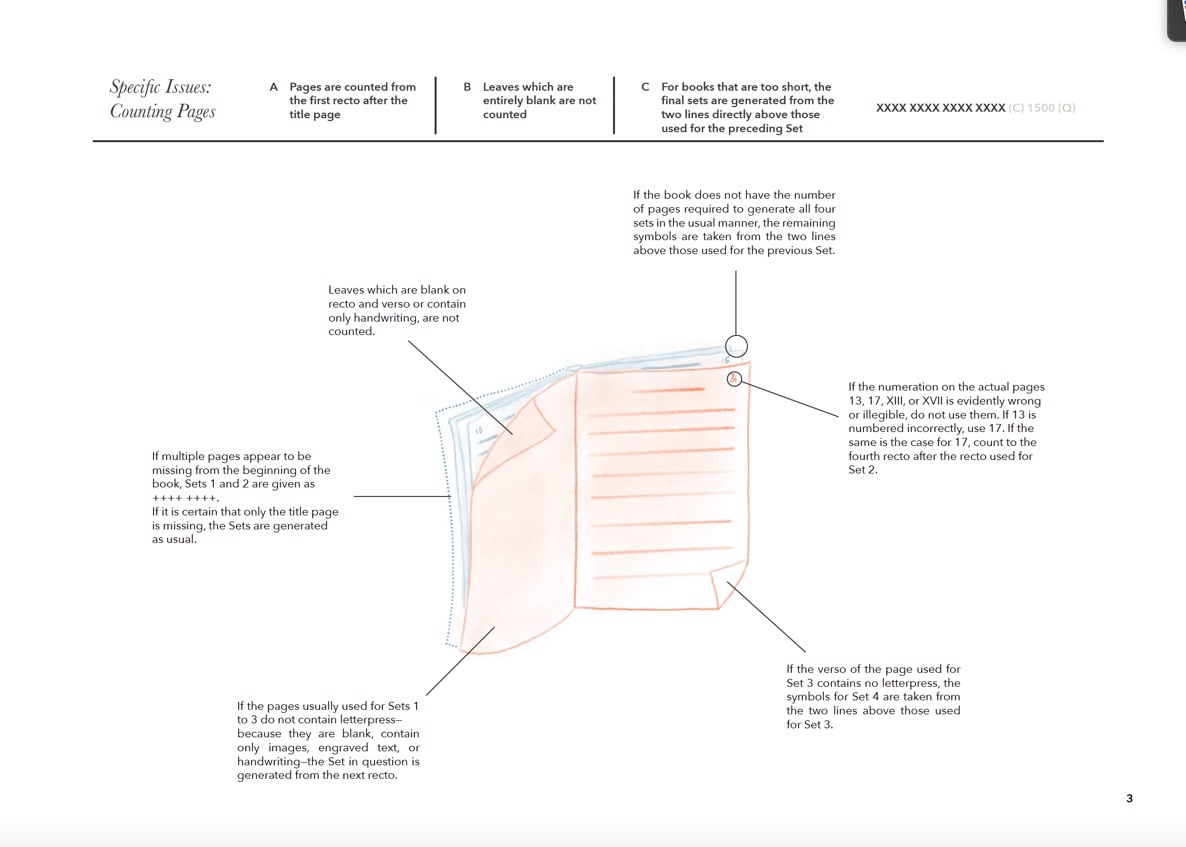

Detail of the graphic workflow to extract fingerprints from early modern prints in order to recognize whether different editions or parts of books were in truth produced in the frame of the same print-run.

In addition, a further dataset has been created to model all sorts of social, institutional, and economic relationships between the main actors behind the production of the treatises under investigation: printers, publishers, and authors, who were also university lecturers. To realize this dataset, fingerprints of the treatises—that is, data extracted from material book exemplars and that enable the identification and comparison of books without reference to their bibliographic metadata—were extracted. This makes it possible to flag publications likely to be of similar or identical content and physical composition: for instance, if they belong to the same print run, despite being sold by different printers with altered title pages. The method of fingerprint extraction, originally developed by the EDIT 16 database, has been further developed and a manual by Victoria Beyer, How to Generate a Fingerprint, produced. The ultimate goal of this endeavor is to analyze statistical correlations in content-driven and social datasets to determine the relationships between the emergence of epistemic communities and the societal behavior of the actors involved.

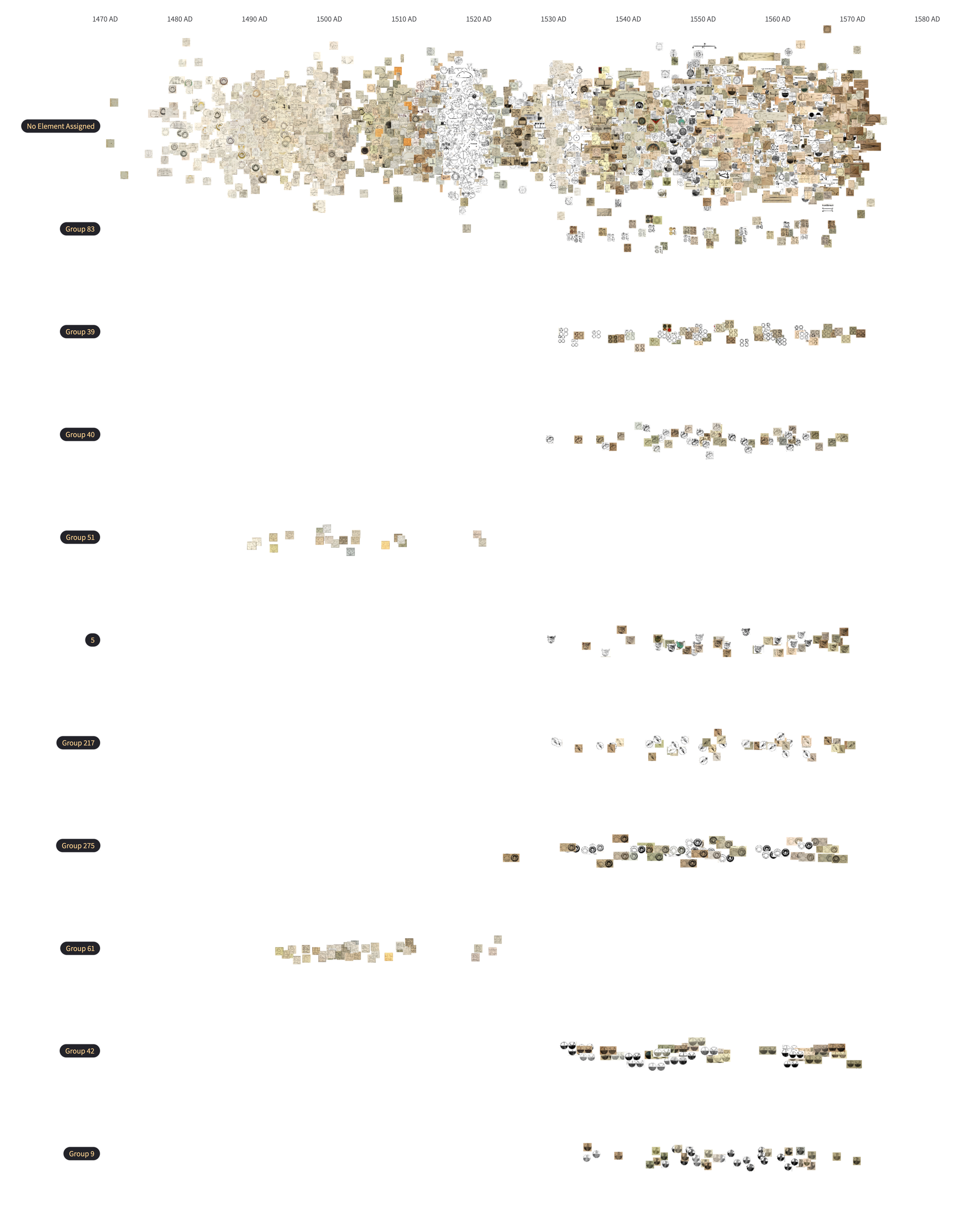

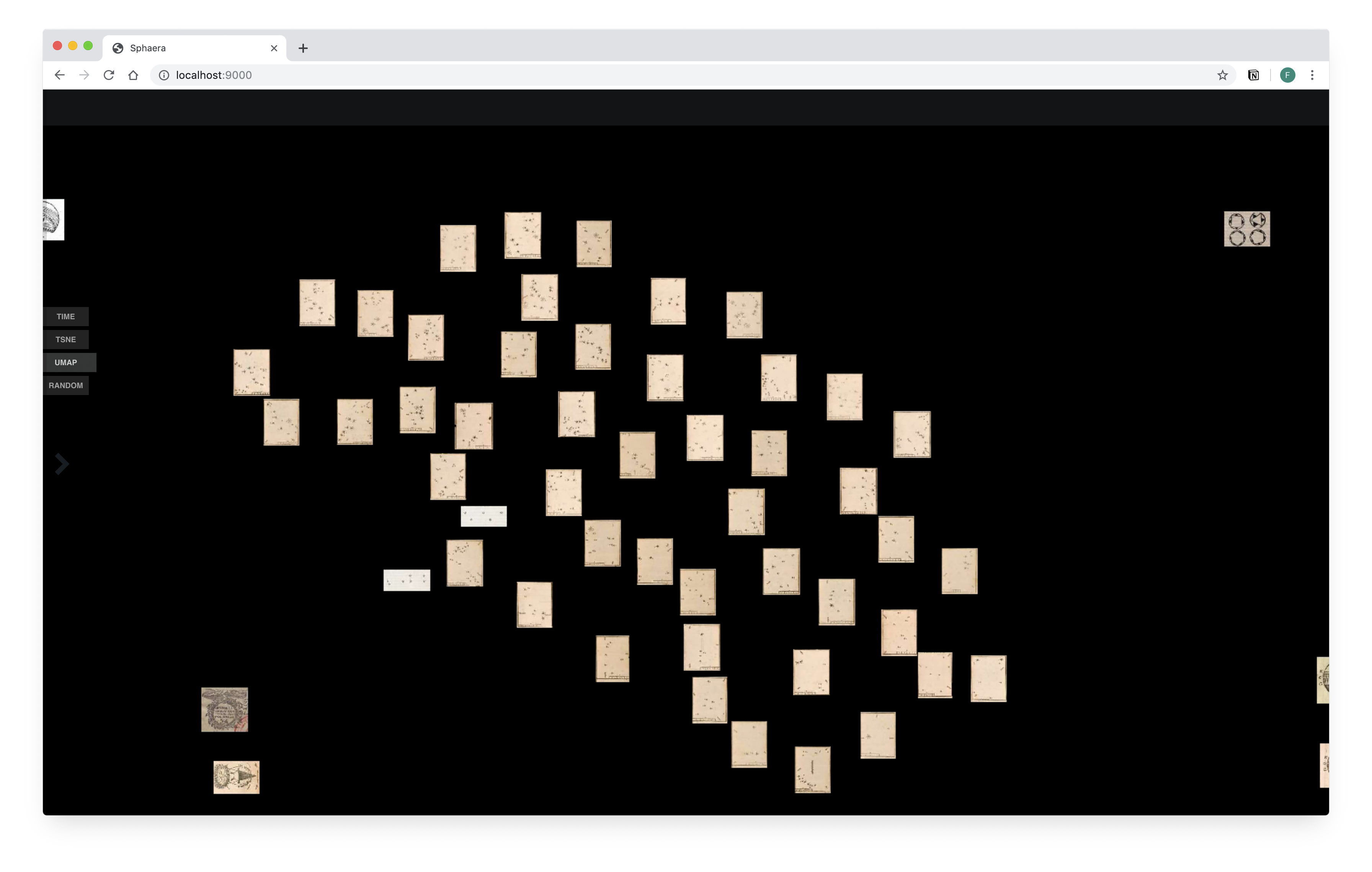

We can identify similar illustrations in our corpus using methods from computer vision and visualization tools. Two existing visualization tools were adapted and repurposed: Coins, developed by Flavio Gortana for visualizing a numismatic collection, and VIKUSViewer, a generic visualization tool for cultural collections developed by Christopher Pietsch.

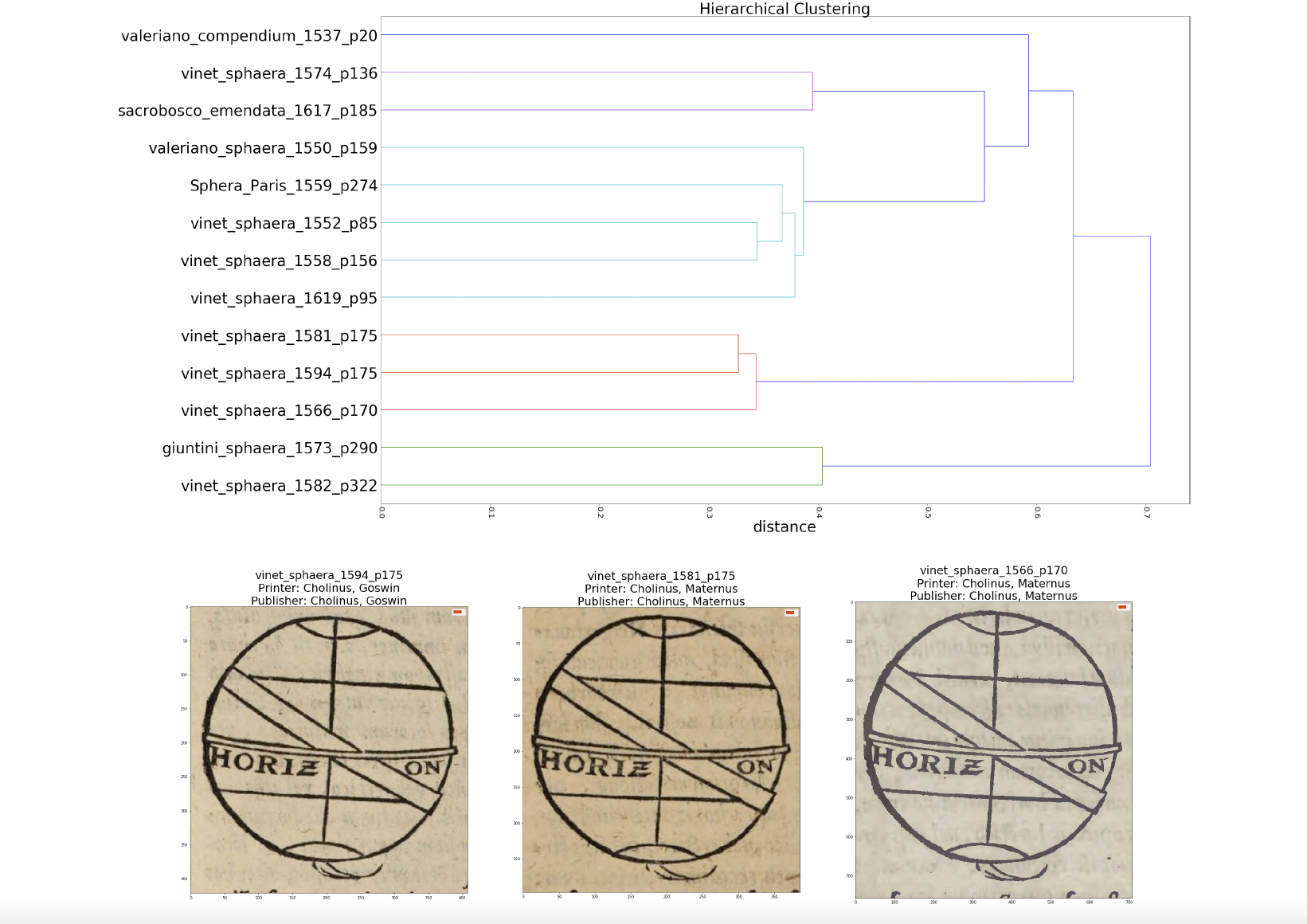

A group of similar, but not identical content illustrations in the Sphaera corpus. We identify such groups by clustering feature representations of the images generated by means of a convolutional neural network. Alongside illustrations originating from the same print woodblock, the groups contain illustrations that were produced by copying an already existing design. In the the latter case we can assume that the content to be illustrated by copy was similar to that by the original illustration. We thus retrieve what can be referred to as groups of "semantically similar" illustrations.

Scaling up: The Berlin Center for Machine Learning

Beyond data extracted from the textual sources, the project focused also on different knowledge carriers: as part of the Berlin Center for Machine Learning, algorithms were developed to automatically identify and extract illustrations and tables from the historical sources. This has led to the creation of a corpus of around 29,500 images—21,000 content illustrations, plus initials, title pages, frontispieces, decorations, and printer marks—and 8,000 astronomical tables. Our current and future work involves the development of a series of algorithms to cluster these data by their similarities defined in dependence from the historical research questions. Our ultimate goal is to enrich the knowledge network through new graphs that represent the entirety of the historical sources’ contents, to finally explore the possibility of modeling the network in its entirety, and to be able to compare the evolution of knowledge with other evolutionary processes such as those described in the frame of evolutionary biology.

A group of similar, but not identical content illustrations in the Sphaera corpus. We identify such groups by clustering feature representations of the images generated by means of a convolutional neural network. Alongside illustrations originating from the same print woodblock, the groups contain illustrations that were produced by copying an already existing design. In the the latter case we can assume that the content to be illustrated by copy was similar to that by the original illustration. We thus retrieve what can be referred to as groups of "semantically similar" illustrations.

We further quantify the similarities amongst the items in a group of semantically similar illustrations by applying an image similarity measures from the field of computer vision. Clustering by this similarity measure, we able to distinguish illustrations that stem from printing with the same woodblock. Above: Dendrogram of the hierarchical clustering of the items of one the groups of semantically similar illustrations: Below: One of the subgroups generated by this clustering. The information that the same woodblock was used in printing these illustrations is contextualized by correlating it to metadata, thus allowing for contextual inferences. The example at hand provides evidence that Goswin Cholinius continued to operate the printshop of his father Maternus.