My project addresses a consequential gap within the historiography of medicine and the biomedical sciences, namely the challenges posed by the high degree of medical intervention for clinical decision making. I will explore the intervention-driven transformation of diseases, bodies, and populations, focusing on American and European medicine over the last 50 years.

To situate these challenges, I first explore different attempts to define and conceptualize clinical judgement in Anglo-American medicine since the late nineteenth century. I then examine the ways that the straightforward “translation” of evidence from clinical experiments to clinical decisions has been undermined in our highly intervened-in world. These challenges include increased patient idiosyncrasy; the widened gap between experimental subjects and actual patients; the short half-life of efficacy knowledge imposed by continuous practice innovation; the problematic efficacy of interventions which work by impacting other interventions; the difficult task of distinguishing the effects of interventions from those of disease; the increasingly blurred boundaries between research and practice; and the problematic reliance on data (big and small) from clinical practice to evaluate the safety and efficacy of interventions.

These challenges have led to more rationalistic modes of judgement even as Western medicine celebrates the ascendency of a highly empirical “evidence-based” medical practice. They have also transformed care, which increasingly involves navigating access to interventions and dealing with their bodily and bureaucratic complications.

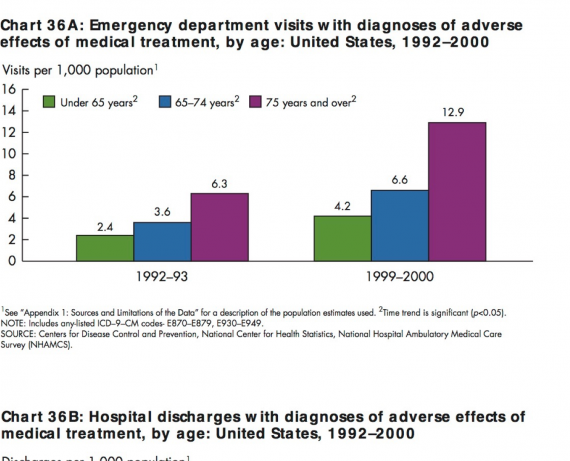

Problematic trend. What are the causes? Implications for clinical judgement?

Emergency department visits with diagnoses of adverse effects of medical treatment, by age: USA, 1992-2000. Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS).