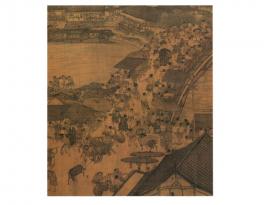

Imperial officials of the Song Empire (960–1279 CE) confronted a complex, monetized society. The colonization, between the ninth and eleventh centuries, of the well-watered lands south of the Yangzi River had increased agricultural production, which set in motion a progressive spiral of market formation, regional specialization, population growth, and urbanization. To facilitate the movement of goods from the countryside into the cities, the government dredged rivers, dug canals, maintained roads, and introduced the world’s first paper money.

Rather than celebrating these developments as evidence of progress and human ingenuity, however, imperial officials fretted that the confusing movement of people, goods, and money obscured the immanent patterns of human society that the ancient sages had articulated in text and in ritual. Imperial officials determined to rediscover these patterns, so that they might restore to the lapsed present the perfect governance of antiquity. Because they perceived that commerce circulated goods to supply elemental needs, they were convinced that money and trade were part of the natural order. And because money and trade were part of the natural order, officials sought to understand their principles by analogy with other natural phenomena, such as the flow of water and bodily circulation.

"The City as Nature" will make this political and philosophical history vivid by focusing on the emergence of the city into writing. The project will demonstrate that during the eleventh century, the commercial cityscape became an acceptable topic for literary composition as literati attempted to encompass the city within nature, as part of their effort to discover the inherent patterns of human behavior. In their poetry and prose, the commercial cityscape emerges not as an achievement of human artifice, but as a living organism, where traffic flows like water, goods circulate like the vital essences of the body, and trade flourishes like a well-tended garden.