"The science of farming is a science full of benefits; it is the origin of all industries." ʿ ilm-i filāḥat ʿ ilm-i pür menāfiʿ ve aṣl-ı cemi-i ṣanāyıʿ, Nevi Efendi (1533/4–1598)

Agriculture essentially means reducing complex ecosystems to controlled habitats for a few selected species of plants and animals. It encourages meticulous observation of natural patterns, and its improvement and stability often provide the backdrop for experimentalism and natural history.

This working group explores pre-1700 agriculture in its foundational role in informing emergent “sciences” globally. Agriculture is treated as a body of knowledge through which humans learned about their environment; the migration of ideas and practices are traced from texts to other epistemological spaces, from one ancient agriculture and culture to another. We trace the development of material practices following the Chinese concept of five phases: soil (tu), water (shui), metals (jin), fire (huo), wood (mu). By studying historical relationships between knowledge practices and environmental change, the working group contributes to the study of science, technology, and medicine, as well as debates in global history.

In the first phase, under the theme "Soil," this working group explored how the quotidian labor of the field informed the disparate ways of organizing knowledge across the premodern and early modern world.

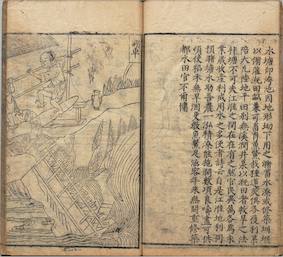

Dedicated to the theme "Water," the second phase focuses on agriculture and water control, exploring the interplay of technology and political processes in Song, Yuan, and Ming China.

With its new theme "Metals and Minerals," the working group is entering its third phase.

Recent Activities

Reading Group “Agriculture, Metrology, and Statecraft in the Sinographic World, 1000–1850,” held on every other Tuesday from 15:00–17:00, beginning January 23, 2024.

Reading Group “Agriculture in the History of Science,” held fortnightly on Fridays, November 11, 2022–February 10, 2023.

News & Upcoming

Edited volume in preparation, edited by Justin Niermeier-Dohoney and Aleksandar Shopov: Toward a Global History of Soil: Sciences, Practices, and Materialities in the Early Modern World (Brill, forthcoming).

The group has partnered with Brill to launch the book series Agriculture and the Making of Sciences, 1100–1700: Texts, Practices and Transcultural Transmission of Knowledge in Asia.

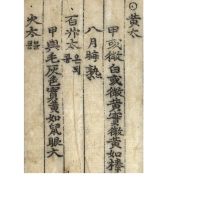

A chain-pump depicted in Wang Zhen’s Nongshu (“The Book on Agriculture”), first published in Yuan-period China. Source: open access, the Naikaku Bunko Collection, National Archives of Japan Digital Archive (https://www.digital.archives.go.jp/das/image/F1000000000000099582)