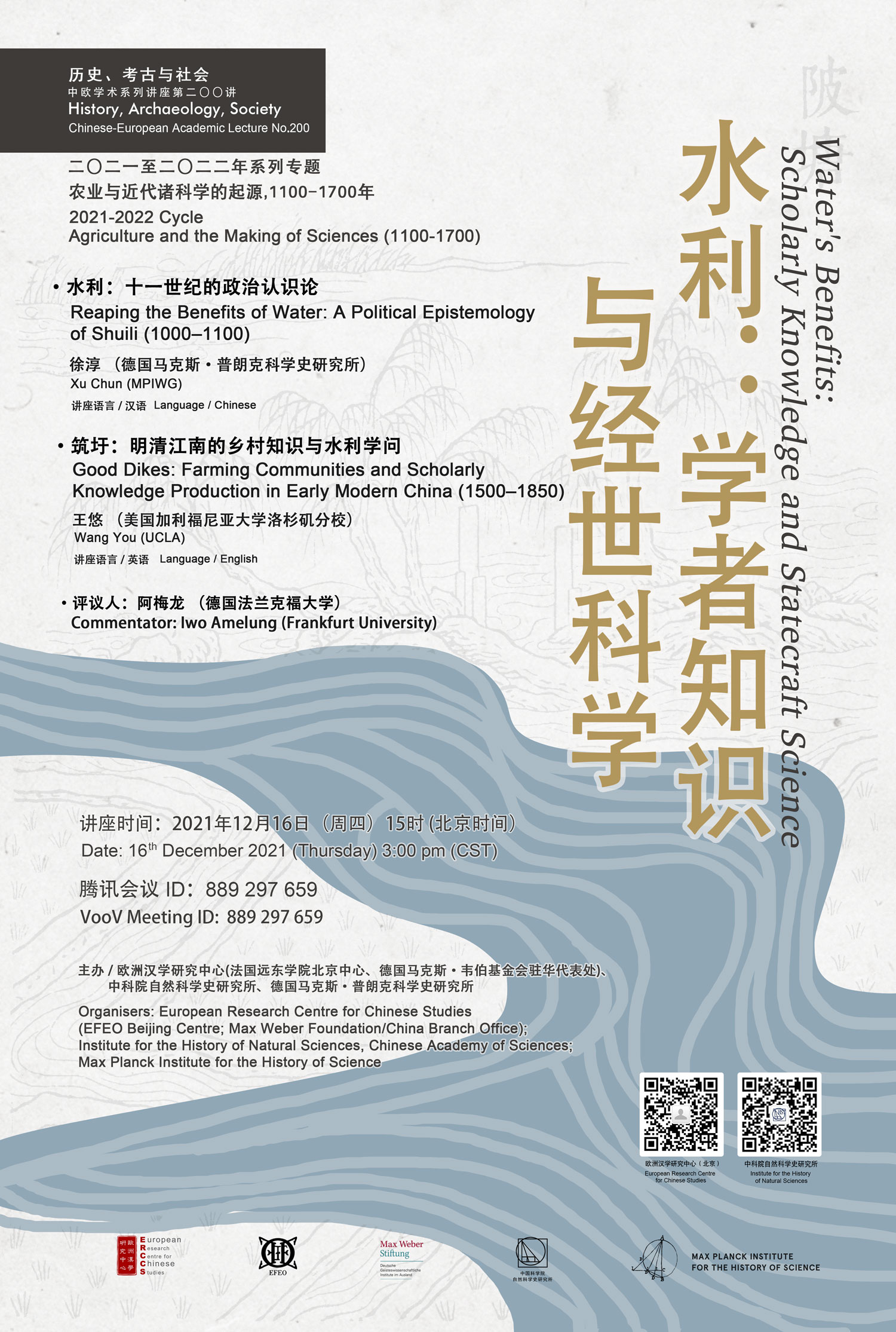

Dec 16, 2021

Water’s Benefits: Scholarly Knowledge and Statecraft Science

Reaping the Benefits of Water: A Political Epistemology of Shuili (1000–1100) (Xu Chun)

In the eleventh century, the language of shuili, or “reaping the benefits of water”, gained political salience. This research situates the concept of shuili in the context of the Xifeng Reforms, foregrounding the practical knowledges and technologies that informed the particular meanings of shuili. The reformists’ idea that the state should actively reap the benefits of water, among other resources Heaven and Earth could offer, symbolizes a rearticulation of statecraft since the early years of the Song. Whereas the New Policies faction actively employed emerging technologies of statistics, cartography, topography and agronomy to advance their shuili programme, the conservatives disputed the validity of shuili as a category of knowledge and legitimate political action. Nonetheless, the vocabularies of shuili created, and the technologies of shuili materialized, a domain of statecraft in which state intervention was called for and could be exercised.

Good Dikes: Farming Communities and Scholarly Knowledge Production in Early Modern China (1500–1850) (Wang You)

Jiangnan (the Greater Shanghai Area today) has been China’s economic and cultural center for nearly a millennium. Since at least the eleventh century, scholars had debated over the best measure to engineer local waterscape. In its lowland, polders — arable land enclosed by dikes — were crucial to protect rice paddies from flooding and ensure agricultural harvest and economic prosperity and thereby at the center of scholarly discussion.

This study examines the efforts to explore and promote proper dike-building techniques in Jiangnan’s lowland between roughly 1500 and 1850, a period loosely referred to as early modern China. In particular, it investigates two analytically distinctive but practically intertwined approaches to produce agricultural knowledge and build dikes — the external approach advanced by outside scholars and the communal approach by some residential landowners. In the external approach, scholars viewed rural communities as part of the problem and attempted to impose strict and universal dike standards over “lazy farmers” and discipline farmer-laborers via compulsory official powers. Especially in the early nineteenth century, a new approach to waterscape engineering occurred. Refusing the standards of effective dikes set by outsider knowledge, practitioners of this approach trusted farmers with their in situ knowledge and critical skills best able to design their own dikes. Rather than attempting to coerce farmers to work arduously under official supervision — what James Scott terms “seeing like a state” — this communal approach acknowledged the multiple tasks farmers routinely faced and attempted to minimize dike-building workload while ensuring necessary hydraulic maintenance. Based on the cumulative experiences of farming communities, the communal approach attempted to achieve an optimal alignment between feasibility and outcomes. The faceless “idle” farmers in the earlier agronomic and hydraulic discussions were transformed into active agents of knowledge with relevant experience in lowland waterscape management.

Contact and Registration

The seminar is open to all. To register, contact Chun Xu (cxu@mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de).