This project focuses on a historical moment when noise was a political concern. During its first decades, the 1950s and 1960s, Radio Free Europe (RFE) developed methods of studying noise that hindered clear radio signals behind the Iron Curtain. RFE faced constant uncertainty about sound clarity. Due to political constraints, its transmission facilities operated from West Germany and Portugal, technically unfavorable positions for reaching its intended listeners. Communist governments used jamming to combat “enemy propaganda,” while solar activity also affected the ionosphere and the quality of radio signals. Politics and nature, then, both distorted sound.

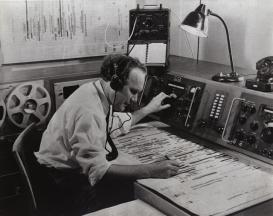

For the RFE team, noise was not meaningless or irrational, but an object of research with its own rules. Through its multidisciplinary research, RFE tried to demonstrate that broadcasting could overcome noise and that political messages were reaching potential dissidents. Experts from various fields gathered acoustic information: RFE engineers reported on mechanical sound levels, meteorologists assisted in distinguishing jamming from atmospherics, and RFE sociologists used surveys to seek patterns of radio listening amid jamming. Based on primary sources at the Blinken Open Society Archives, my project examines links between sound, politics, science, and culture in the RFE context. How was acoustic information about noise transformed into visual symbols, numerical codes, and charts? To what extent was radio sound clarity used as an indicator of political trends in communist countries? These and related questions are addressed in my study of the historical trajectories of distorted sound.