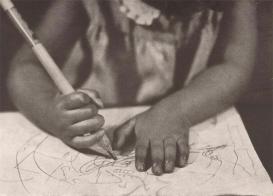

The institutionalization of child psychology around 1900 was accompanied by techniques of observation and experiment that separated scientific attention from the education and everyday care of children. The experimental application and interpretation of children’s drawings became one of those techniques. Whereas before 1880, children’s drawings were seen as mere scribbles, and not considered to be of any aesthetic or heuristic value, psychologists such as James Mark Baldwin, James Sully, William Stern, Ernst Meumann, David Katz, George-Henri Luquet, Karl Bühler, Florence Goodenough, Sophie Morgenstern, and Jean Piaget soon after came to consider drawings to be a major diagnostic device in the investigation of children. Like children’s play and their stories, the “artistic production” was (and still is) believed to reveal sensomotoric functions and perceptions of space, to give proof of children’s intelligence and social development, and to document their psychoanalytic dispositions and symptoms.

The emergence of children’s drawings as diagnostic tools was supported by different kinds of methods, techniques, and tests, which were developed to “read” that which previously had been “meaningless.” These interpretative practices had to control the dynamic of drawing and the transference between the child and the scientist. The experimental setups and tests framed and stabilized the scribbles: certain qualities of children’s drawings were isolated, single gestures/motifs repeated again and again. In this way, psychology began to conceive of children’s drawings as a more or less orderly (or well organized) process, which through its very regularity enabled the visualization of irregular psychic symptoms and dysfunctions. Therefore, children’s drawings were applied in the way of a veritable “Verfahren,” i.e., they were embedded and transformed into a calculated procedure that allowed the scientist to be diverted und surprised by unexpected phenomena.

The operationalization of children’s drawings in psychology is certainly a special—and somewhat strange—case in the history of drawing as a scientific instrument. Whereas all other kinds of scientific inscriptions are produced by a scientist, his assistant or a commissioned artist, children’s drawings can only be made by the scientific object itself. Of course this does not mean that we should consider the psychometric or psychoanalytic products of drawing children as immediate “self-portraits.” The drawings made in experimental and diagnostic contexts do not contribute to the constitution of subjectivity directly, but to its mediation and objectification. The historical reconstruction of the experimentalization of children’s drawings around 1900 illuminated the practices and methods through which an everyday artistic activity was transformed into a research technique and how it shifted between these functions.