In the mid-nineteenth century, the third expanded edition of the Literary and Philosophical List or Catalogue of All Research Published To Date On the Subject of Deaf-Mutes, the Ear, Hearing, the Voice, Language, Mimicry, and the Blind affirms the fundamentally interdisciplinary approach to the study of those referred to at the time as the “deaf-mutes.” The bibliography by C. Guyot and R. T. Guyot (Groningen 1842) collates various Latin, French, German, Flemish, English, Spanish, and Italian works, on nearly 500 pages. The fruit of the labor of two brothers—one a medical doctor, the other a doctor of law, and both teachers of the deaf—the bibliography seeks to validate the multiplicity of approaches pursued at the time. Its two authors present its translation into French as a sign of the publication’s international significance, and address the preface to their colleagues abroad. They thank several statesmen, men of letters, and the directors of institutes for the deaf in Europe and in America for having contributed items to the project. They request further corrections, and insist on the importance of writing a history of the education of the deaf-mute since its earliest days. One is struck instantly by the geographical, historical and thematic scope of the work: the study of the deaf-mute aspires to transnational import, and seeks to embed itself in a narrative: the point thereby being to establish the broader questions to which the designation “deaf-mute” gives rise. The authors favored a systematic rather than chronological approach. Works devoted to the instruction, the “character,” and the social and “moral constitution” of the deaf-mute are addressed in the first section, and likewise their teachers and institutional provision. After that comes a compilation of medical treatises concerning the ear and hearing and their potential defects, experimental treatments for deafness such as electricity, perforation of the mastoid apophysis, perforation of the ear-drum, catheterization of the Eustachian tube, and animal magnetism. Body language is the focus of the third section, a catalog of works on the art of mime, pantomime, the art of oratory, and the art of physiognomy. The study of language is detailed in the fourth section, and a distinction made thereby between its origin, the notion of a universal language, general grammar, syntax, ideology, signs, the relation between signs and sensation, “the language of savage man,” writing and written characters and, finally, the so-called artificial languages such as telegraphy, dactylology and stenography. The work concludes with a bibliography devoted to the blind. Certain titles recur in different sections, testifying to the authors’ endeavor to make each exhaustive. The methodical and repetitive character of the work also serves to illustrate the overlap and interweave of the various fields of knowledge developed until then.

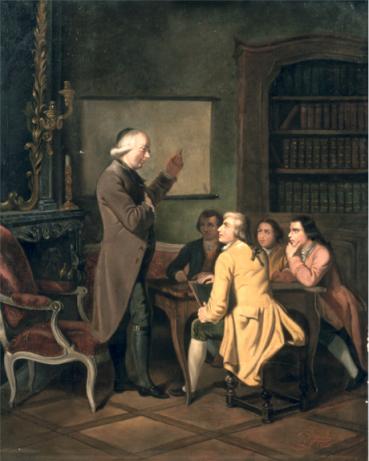

Fig. 2: Nachor Ginouvrier: Leçon de l'Abbé de l'Epée, Institut National des Sourds-Muets (Paris).

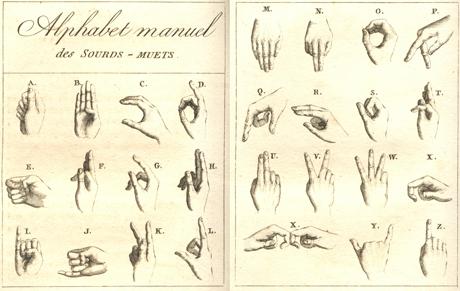

Yet, little more than a generation later, the encyclopedic scope of such work was challenged. In 1880, at the close of the Milan Congress, a person’s relationship to speech was supposed to be primordial. Doctors there considered the deployment of a variety of instruments as the key to the problem of deaf-muteness. Otology held forth as a science fit to challenge more than 250 years’ practice of dactylology (which represents each letter by a hand gesture) and almost as many years of chironomia (which represents an expression by a hand gesture). The doctors dismissed the use of sign language as a waste of time and, moreover, as a cause of isolation. The increasingly complex terminology employed in prior years to describe deafness and muteness, and to debate their possible causes, made of both conditions a problem treatable by a range of instruments likely to be perfected in the near future. Medical knowledge established its authority by determining a norm for humankind. Re-education of the deaf became thus the doctors’ prerogative. And Lannois, a doctor of medicine, enjoined shortly afterwards: “Let him reconquer language so that he might affirm his thoughts, his will, and his heart.” The conclusion reached by the Congress was endorsed by new legislation prohibiting the instruction of sign language in several European countries. Prohibiting the instruction of sign language simultaneously decreed the legal suppression of muteness.

Paradoxically, in 1880, if one believes the medical examiners, the deaf-mute was much more than a man who neither hears nor speaks—or even less. Numerous texts were devoted to maligning his character, or to attributing him psychological depth. Since publication in the early 1800s of Jean Itard’s essay on Victor, the wild child of Aveyron—tellingly a case that remains a cause célèbre to this day—countless doctors and educators have published extensive details of their experience with the deaf-mute. Each of them endeavors to trace the parallels between impaired hearing and the absence of moral values or social skills. Countless doctors present the deaf person as an “incomplete” individual who ranks categorically among the abnormal.

To define the deaf-mute, his development, and his need to advance, is to define who has a right to speak about the deaf-mute. It is to define whether he should be cured, how best to improve his quality of life or his chance to play a role in society, and it establishes that society has a responsibility toward him. In defining a physical handicap, these texts seek also to define who is an expert on that physical handicap. This gives rise to as many issues as disciplines destined to reflect on and resolve them: auditory, moral, mental, legal, educational, social ... while various texts permit each of these competent persons or bodies to develop and wield authority.

Fig. 3: Edouart Hocquart: L’art de juger du caractère des hommes sur leur écriture. Paris 1816, plates 1–2. The Blocker Collection, Moody Medical Library, The University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston.

This research traces the diverse ways in which a different auditory threshold has come to represent a problem in need of a cure, as well as how conceptions of the problem in philosophical, medical, and legal discourses shifted over the course of three centuries. It seeks to establish how hearing speakers have defined a person’s relationship to language as the starting point of an understanding of humankind. It is by examining this understanding in the light of an analysis of the written word that the work pursues its various trajectories. The objective is to analyze how political, epistemological and cultural stakes are inscribed in the formulation of ideas, and in the choice of the terms employed, the imaginaries invoked, and the definitions proposed. The aim is not so much to write a history of actual ideas and experiments but rather, a history of how these are articulated and received. To analyze their articulation and reception is simultaneously to take account of the conceptual choices that shape the construction and dissemination of various bodies of knowledge, and the education of the people whom these are intended to reach.