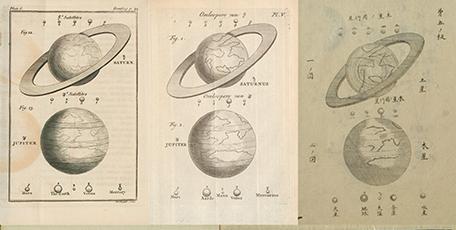

A convoluted course of illustrations led to Copernican Astronomy Illustrated (1808) in Japan: an English treatise on the construction of globes by a royal instrument-maker; a revised translation of this treatise in Amsterdam; manuscript excerpts from the Dutch text made by a Nagasaki interpreter; images from this manuscript copied into Shiba Kōkan’s notebook; carvings on woodblock, reimagined from Kōkan’s notes, used finally to print the illustrations of Copernican Astronomy (Fig. 1). Such once was the fate of images transmitted across long distances, from engraver’s burin, through calligrapher’s brush, to xylographer’s knife.

Fig. 1: The five stages of image transmission from London to Japan. From top left: George Adams, A Treatise Describing the Construction and Explaining the Use of New Celestial and Terrestrial Globes, 2nd ed. (London, 1769), ETH Zürich; Jacob Ploos van Amstel, Gronden der starrenkunde (Amsterdam, 1770), ETH Zürich; Motoki Ryōei, Shinsei tenchi nikyū yōhō ki (1793), Waseda University Library; Shiba Kōkan, Shunparō tenmon no sho sōkō (ca. 1805), Waseda; Shiba Kōkan, Kopperu tenmon zukai (1808), Waseda.

Fast forward to 1910, and we see a differently convoluted transaction. Writing to Wilhelm Wundt for permission to translate the Grundzüge der physiologischen Pyschologie (1873–74), the Japanese psychologist Motora Yūjirō was informed that rights would be given only if electrotype reproductions of the book’s illustrations were purchased directly from the Grundzüge’s original publisher. The Japanese protested the expenses; the Germans argued that this would assure the accuracy of illustrations. Negotiations fell apart. No Japanese translation of the Grundzüge was ever produced.

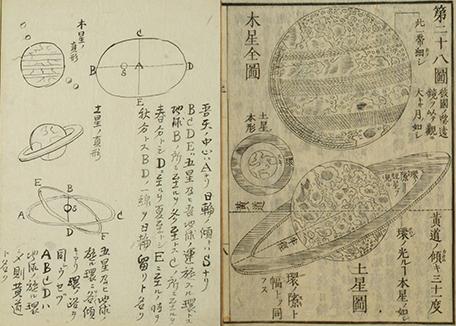

What had changed? At the beginning stood electrotyping and stereotyping, allowing publishers to easily stockpile images for duplication, and giving birth to what we now recognize as stock image banks. As early as 1826, the publishing house Hachette had already launched a Service des illustrations, cataloging their stock of images by topic and licensing out stereotyped copies to other printers. Soon after, Harper’s constructed a subterranean vault for electrotypes, with shelves eight feet high running 200 feet under the streets of New York City. By 1855, it held over 10,000 electrotypes, at an estimated 70 tons (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Harper’s underground electrotype vaults. Source: Jacob Abbott, The Harper Establishment (1855).

Although images had long circulated through varied means of reproduction, the rise of electrotype image banks standardized this circulation as a legal-commercial practice. Combined with international copyright regulations, plates offered authors and publishers better control over their images abroad. Against complaints that translations for distant markets featured “abominable illustrations” miscopied from originals, contracts stipulated that publishers of translations also purchase electrotypes of the original illustrations.

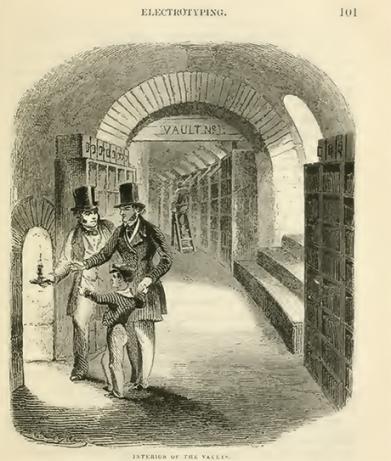

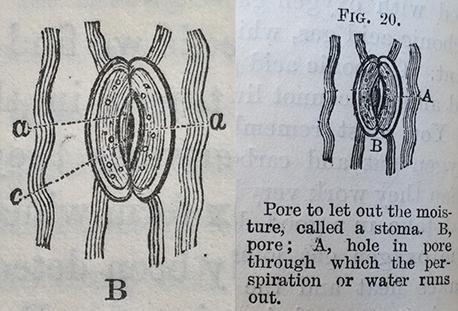

Simultaneously, the growing availability of plates for all occasions inclined publishers to source illustrations from existing works, rather than invest in new ones. Longman’s Town and Window Gardening (1879), for example, was illustrated with electrotypes purchased from six other publishers. So it was that a guide to the art of window garden-boxes shared the visual vocabulary of botanical textbooks and Darwin’s Fertilisation of Orchids, among others (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3: Examples at left of illustrations from Carpenter’s Vegetable Physiology (1847), electrotypes of which were purchased by Longmans for Town and Window Gardening (1879), at right. Note the modifications, particularly in the second set, where one can one can still detect traces of the lines for (a) and (c) in Carpenter that have been erased. Source: British Library.

While the economy of electrotypes took form, inventors were devising tools of transmission more efficient than heavy plates. Since the advent of the telegraph, it had been hoped that the electric clicks of Morse code might one day be replaced by graphic representation. Indeed, the early twentieth century’s dream of picture telegraphy—one only fitfully and imperfectly realized over subsequent decades—occupied a key position in discourses on the place of images in international communication. Arthur Korn, architect of modern fax technology, understood picture telegraphy as providing instant, more accurate information concerning distant locales. East Asian audiences hailed picture telegraphy as an overcoming of Eurocentric biases in communication technologies, bringing language from alphabetic back to ideographic.

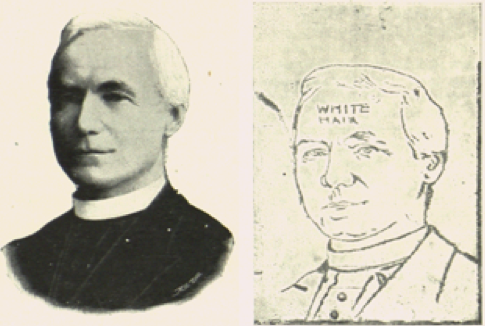

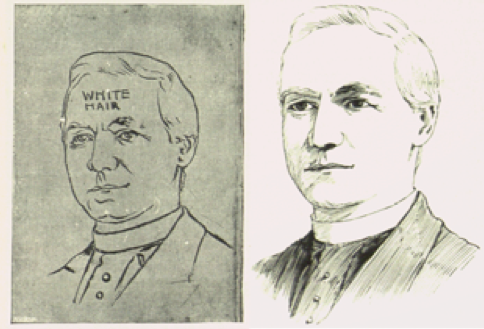

From electrotype to the electric image, the new accuracy and speed of long-distance graphic transmission promised a global unity to vision transcending linguistic differences. Yet fundamental ambiguities remained. Color, for example, proved a recurrent dilemma necessitating the use of words, as seen in this telediagraph sequence (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4: Stages of transmission by telediagraph from Washington, DC to the offices of the New York Herald. As the telediagraph could not transmit color, the sending party inscribed “white hair” on the image for the benefit of the receiver. Charles Cook, “Pictures by Telegraph,” Pearson’s 3:4 (1900).

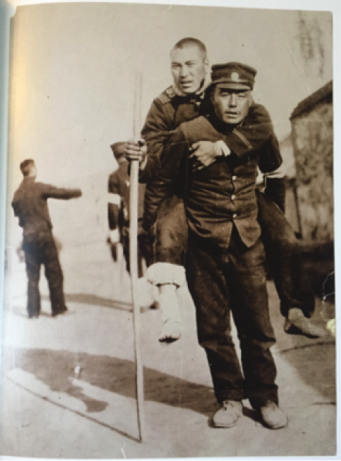

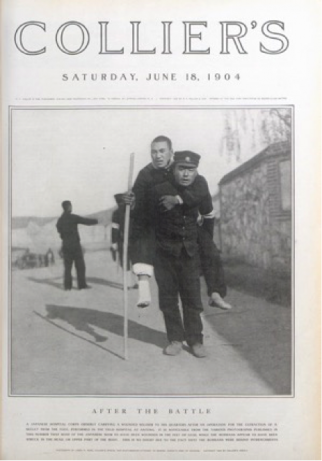

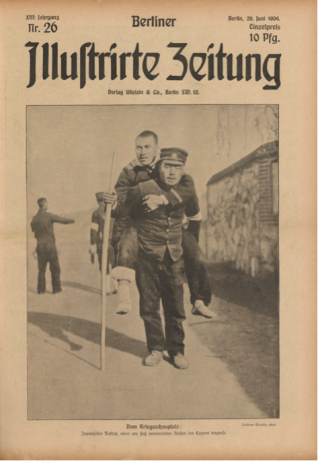

And what of Korn’s hope that picture telegraphy would provide more reliable news of distant lands? Consider this photograph from the Russo-Japanese War in 1904, as it made its way to New York and Berlin. According to Collier’s Weekly, it depicted a Japanese orderly carrying one of his own wounded countrymen. But according to the Berliner illustri[e]rte Zeitung, the same photograph depicted a Japanese soldier benevolently carrying a wounded enemy Russian (Fig. 5).

Fig 5: Photograph from the Manchurian front (left). Its first reproduction (right) in Collier’s is captioned as a Japanese orderly carrying another Japanese soldier. The caption of the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung (bottom) instead claims that the Japanese soldier carrying an injured Russian enemy soldier.

As I continue my research, I thus aim to inquire not only into the technologies and economies for the global provision of images, but also into the practices of truth and meaning that emerged alongside these. What strategies were deployed to stabilize visual meaning and make concrete claims in a world of ever more mobile and ubiquitous images? These questions place my research into closer dialog with our contemporary crisis where, surrounded by visual communication, from the emoji to Instagram, we are increasingly unsure of what an image tells us of reality.