Medieval Eurasia witnessed widespread circulation of knowledge and beliefs about the visible heavens, the character and consequences of which are in many ways just beginning to be understood. This is particularly true for Sinitic and Inner Asian cultures, where local processes of reception were heavily mediated by older, indigenous systems for knowing the heavens and predicting or controlling the future. Thus, the Hellenistic zodiac, for example, became in China an important chronomantic unit disconnected from the visible constellations of Western Eurasia. Visual and material culture offers unique insight into processes of substitution, correlation, accretion, and translation, often complicating the stories presented in texts. For example, although iconographic elements in depictions of the zodiac and planetary gods may appear relatively stable from culture to culture, their disposition within a given representational context often speaks to fundamental conceptual transformation.

This project examines how the heavens were described, modeled, and invoked in ca. tenth- to fourteenth-century China and Inner Asia according to several major subtopics: the Sinitic uranographic tradition, Buddhist and Daoist astral cults, the Hellenistic zodiac in East and Inner Asia, and the material culture of astronomical instruments. Particular focus is given to the Tanguts, Tibeto-Burman founders of the Xixia state (1038–1227) who left behind a dense record of astral worship and unique or otherwise lost documents of trans-Eurasian knowledge circulation. At issue is not only the who, what, and when of knowledge circulation, but also how such processes came to transform the nature of representation itself.

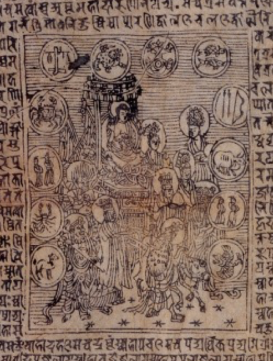

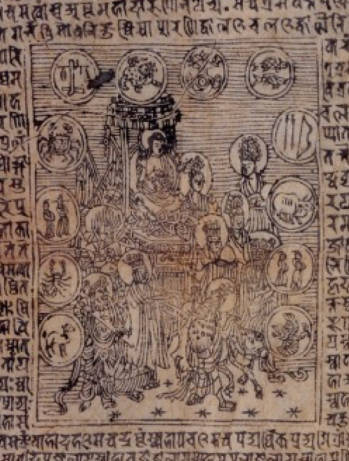

Tejaprabha Buddha, the Nine Planets, and the Twelve Zodiac Signs. Xylograhphic amulet print found in the Ruiguang pagoda, Suzhou, China, 1005 CE