Vegetation and vegetative powers, in their ability to preserve, maintain, and reproduce life, have shaped the understanding of living bodies and the definition of life throughout the centuries. The early modern understanding of vegetation and vegetative powers appears particularly significant and innovative. During this period, alternative interpretations of life surfaced, from mechanical philosophy to alchemical traditions, resulting in fierce clashes without a definite solution. Life apparently remained something unfathomable. A theoretical approach to the study of plants—the silent witnesses of life—promised to help remedy the problem, but created new issues that required new investigations.

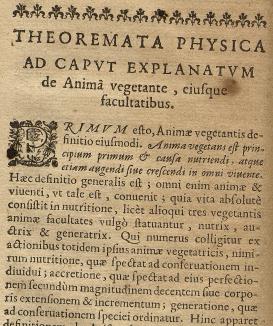

During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, vegetation attracted scholarship not only for the external variety and diversity of plants, but also for their structure and functions. In Aristotelian traditions, the vegetative soul was a principle of the basic activities of life. Discussions of that soul shaped the early modern understanding of plants and life. Scholars shed new light on the understanding of vegetare, of nutrition, growth, and reproduction, but were also interested in physiological and anatomical studies of plants and animals. A philosophical interpretation of plants as representing the minimal level of vitality led to important attempts to redefine life. In my project, I focus on three aspects: the early modern medical approach to plants as a model to explain the basic functions of life, especially describing embryology and the operations of the liver; the reception of pseudo-Aristotle’s De plantis by seventeenth-century botanists, naturalists, and philosophers; and the early modern study of plants and vegetation.