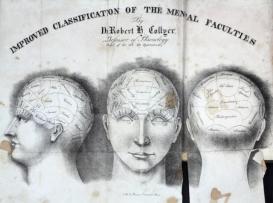

This project examines how phrenological practices depended on paper, or rather, on a system of paper. Considered a science by many in the early nineteenth century, phrenology measured the skull and localized faculties to analyze the brain as the “organ of the mind.” “Practical phrenology” thrived in the antebellum United States amidst growing health reform movements and a flourishing consumer and print culture. While phrenology books abounded, paper charts, individual analyses, notebooks, lecture notes, broadsides, receipts, stationery, and traced profiles worked in tandem to constitute an accessible, transportable, marketable science. And on paper, phrenology sorted people into categories and made normative certain physical and mental characteristics, delineating differences of race, gender, ability, and disability.

This study focuses on how phrenological paper tools of the trade served in measuring, documenting, and evaluating cranial characteristics, particularly in relation to gender. It shows how gender expectations and negotiations were built into phrenological charts, and how gender shaped practices with paper. Analysts expected men and women to be more or less pronounced in certain faculties. At the same time, clients could defy those expectations. Chart scores could either affirm the person’s physical alignment with social codes of gender or suggest that they were in danger of thoughts or behaviors in opposition to their sex. Phrenological organs were often illustrated on paper via an ambiguously gendered symbolical head that could be read as either masculine or feminine. On a marked chart, a consumer confronted the results of their examination and their measurements. Once in the hands of clients, papers tools and texts could also be adapted and interpreted according to clients’ own readings of gender. Ultimately, this project explores how phrenology’s paper technologies, especially illustrated charts, were an “interface” for analysts and clients; they were interactive platforms that often blurred the boundary between producers and users of knowledge.