To render a digital image is not merely to specify an expanse of pixels within the specifications of a format, such as the JPEG’s Y’CbCr scheme. Rendering also establishes conformity between a localized performance and its specification in global technical standards. In so doing, rendering—be it graphical, military, or juridical—produces territories.

Screenscapes: How Formats Render Territories investigates the intertwined histories of computational graphics and territorial articulation, i.e., the media-technical formatting of bodies, instruments, and space. Screenscapes puts forth a global history of how computational media encode the coordinates of political and economic struggle, which live on in today’s digital visual cultures. As an excavation of these struggles, Screenscapes contributes to a larger and flourishing debate around digital visual culture underway in fields including the history of science, infrastructure studies, visual culture studies, and environmental studies.

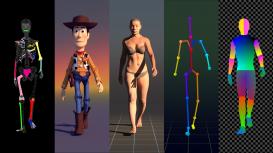

Screenscapes pivots around key case studies of computational instruments for spatial-visual formatting, including eighteenth and nineteenth century astronomical almanacs, mid-twentieth century radar, and early twenty-first century GPS-enabled smart phones. The relations among these (and other) instruments of computational-visual formatting vary widely. Each case carries within it decaying and incipient visualities, variably exhausted and expanding prospects, adopted and adapted by new technical systems according to contingent challenges in war, economics, imperialism, and consumer behavior. Traversing these cases are, moreover, ancillary artifacts, which tend to undo any strict “archaeological” definition of digital visual culture. Among the instances treated in this project: twentieth century ballistics simulators, psychotechnical films for studying radar operators, literary treatments of the seascape by Herman Melville, experimental GPS artworks, popular Pixar films, viral videos from the frontlines of war, and European Community-sponsored studies of visual perception.

Across these disparate cases emerge the broad outlines of what this project terms a “scopic regime of computation” oriented towards a visuality of points, vectors, and ratios. The scopic regime of computation leverages these three features of visual reasoning, less for “representing” or “picturing” events in space than for visually modelling spatial potentiality unfolding in dynamic expanses of space and time. As a scopic regime, the computational emphasis on points, vectors, and ratios forms part of a subtle outline of visual reasoning underpinning fields as varied as architectural design, interactive multimedia consumer devices, viral videos, and environmental modelling.