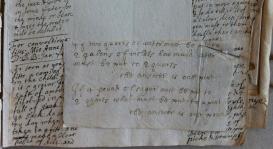

In recent years, the household has emerged as a central place for knowledge codification practices in the early modern period. Investigations into medical and health-related knowledge and practices have proved to be particularly illuminating. Through analysis of a range of sources, such as personal letters, household accounts, diaries, and recipe books, we have uncovered the myriad of ways in which householders sought to understand their own bodies and the natural environment around them. Home-based medical care in the early modern period encompassed a variety of activities—from caring and nursing to diagnosing and prescribing to negotiating medical counters to cultivating medicinal herbs to making medicines. Reading and writing practices were central to these activities. Along with know-how passed down in hushed voices from generation to generation, contemporary vernacular medical print provided many with a firm grounding of practical and, sometimes, theoretical medicine. Householders not only marked up their copies of bestsellers such as Nicholas Culpeper’s The English Physician or the popular recipe book A Choice Manual, but also extracted, summarized, and created external indices in their manuscript notebooks. Additionally, they exchanged medical and culinary recipes on loose paper slips and shared their precious leather-bound recipe books amongst family, friends, and neighbors. Finally, letters containing health-related updates and medical advice fluttered both between family members in informal medical networks and between physicians and their patients.

Paper (and pen) thus played a central role in a number of connected epistemic practices. Householders utilized a range of paper technologies such as notebooks and paper slips to collate, categorize, and manage the vast volumes of medical knowledge they stored in anticipation of possible sickness and ill health. They also used similar techniques to manage, account for, and maintain their social, economical, familial, and knowledge networks. Yet this was not the only medical function taken on by paper within early modern homes. Paper was also utilized in a number of everyday technologies employed by householders for the production of a wide range of medicines and foodstuffs. Analysis of early modern household recipes show that the cheaper rough brown paper was often used to apply plasters, ointments and medicinal waters to the body. Oiled papers were used to shape, contain and preserve rolls of pills. Cap paper was often used to filter and separate liquid mixtures and to protect glass objects. The more expensive white paper was also used in these every technologies; perhaps surprisingly, it was commonly used to dry and preserve fruits and vegetables.

This project investigates the multiple ways in which housewives and household managers used paper “technologies” both in performing quotidian tasks and in codifying practical knowledge. This focus on the materiality of paper, I suggest, offers a new perspective to link the collection and management of knowledge and hands-on practices on the ground. The location of these practices within early modern households enables us to further study how notions of gender might have shaped and framed these practices.