“Climate scientists,” the historian Paul Edwards has recently observed, “are historians” – revisiting the same events, “digging through archives to ferret out new evidence,” without ever obtaining a “single, unshakable narrative.” But centuries before climate change, scholars such as Robert Hooke and later Georges Cuvier spoke of fossils as nature’s monuments and coins. Not merely metaphorical, Martin Rudwick has pointed out that geologists around 1800 drew on the work and concepts of chronologers, antiquarians, and historians to re-formulate the knowledge of the earth as a historical discipline.

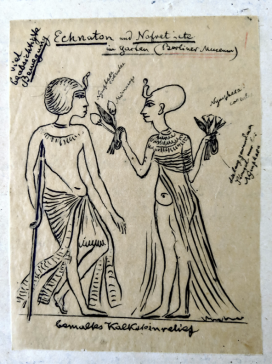

Taking cue from these considerations, I explore how and why the humanities and natural sciences interacted in the writing of deep history. To do this, I am looking at four interlinked cases that took place between roughly 1800 and 1925 in Egypt with forays into the Middle East more broadly. Because many the archaeological remains were so old, they lent themselves to being integrated into the longer timescales of deep time. Thus, for example, we see monuments being used as geo-chronological benchmarks, mummies and plants from pyramids being used to inquire about evolutionary change, and we see both texts and flints launched at the complex issue of Egyptian prehistory.

Much of this knowledge concerned or touched upon ancient agriculture and irrigation and was, therefore, of enormous importance for the various colonial actors on the ground – both practically and ideologically. Throughout the long nineteenth century, modernisation ambitions were framed as the ‘resurrection’ of ancient Egypt. What makes Egypt as a case study in the history of deep time so intriguing, then, is how the past and future were incessantly projected onto each other, pointing to a deeper connection between historical and capitalist developmentalism.

Besides the rich historiography on Egypt in the nineteenth century – especially on various aspects of modernisation and Egyptology – this project was inspired by and seeks to contribute to three further debates. The historiography on the sciences of deep time, firstly, has mostly focussed on the twentieth century and the West, and has mostly neglected the contribution of the humanities to geo-historical theory and practice beyond the eighteenth century and beyond European contexts. The same goes for the newer historiography of the humanities, and this although science-humanities entanglements have recently become a major research focus. Finally, I explore how the emergence of modern historical consciousness in the nineteenth century – a classic theme in intellectual history that has recently been actively renegotiated in the wake of the Anthropocene thesis – played out in disciplines beyond history and territories beyond Europe. Conceptions of deep time, it seems, were decisively shaped by straddling solidifying disciplinary boundaries and by confrontations with non-European contexts