When the second-most-destructive earthquake in Mexico City’s history struck on September 19, 2017, 32 years to the day after the most-destructive earthquake in the city’s history devastated it, residents say that time changed. “Keeping Time with the Earth” treats this less as an ethnographic datapoint and more as a theory of history. Why would an earthquake stop time? What is the relationship between earthly motion and national chronology? How did it begin?

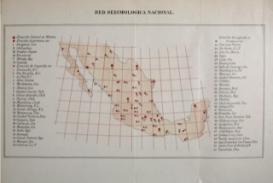

Where most stories about the emergence of the international order of universal time emphasize capital, in nineteenth-century Mexico, the nation’s business owners feared that entering global time would increase the US’ power over Mexican markets. Scientists, however, particularly seismologists, required a universal standard of time in order to triangulate the tremors of their territory with those around the world. Mexico’s participation in universal time arose, at least to some extent, from these efforts to keep time with the Earth. Through haphazard practices such as telegraphing Mexico City from seismic registries in distant states to obtain Mexico’s hour in international time, or travelling from the capital by train with carefully-held pocket watches, these seismologists deployed universal time as if it were delicate object, and slowly brought into being the time of the nation through their efforts to domesticate the time of the Earth. Focusing on data, technologies, and practice, this project will tell a regional history of universal time that foregrounds how temporal imaginations developed as geological time became something to be mapped, measured, and managed.