One crucial question in tracing the history of normalcy is: How does a term come to be established as a category and used to designate something as abnormal?

This research on hysteria, contagion, and Alzheimer's disease showed how much the understanding of a category depends on its configuration in medical records as well as its contemporary use in medical, political, and philosophical debates. Indeed, such categories’ usage seems to play a greater role than their definition, their connotation a greater role than their denotation. By analyzing texts as fields of struggle, the authors saw how particular conceptions come to be shared—to the point of becoming invisible—and taken for granted in discourses and in fashioning sensibilities.

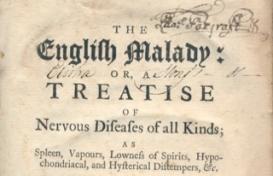

Sabine Arnaud’s work on hysteria was centered on this question. The category of hysteria has attracted a lot of interest, notably because it exemplifies the shift towards modernity, with disorders previously interpreted in demonic or religious terms now being construed as pathological. Yet the moment of the category’s invention, the eighteenth century, has been neglected by scholarship.

Her monograph investigates the writing practices found in medical texts—including the use of metaphors, citations, and literary genres—and how they helped to configure the diagnoses that were later drawn together under the heading of “hysteria.” It further explored the circulation of diagnoses outside the medical corpus and considered the semantic displacement at work in their uses. The book examined contradictory uses of these terminologies and traces how the gaps between approaches were bridged by shared imaginings. Finally, it showed how forging the category of hysteria offered opportunities to define the role of medicine and to establish the status of physicians in society—first giving them privileged access to the aristocracy, and later a mission as citizens in the aftermath of the French Revolution.

In contrast, Sean Dyde's work on hysteria in the nineteenth-Century German lands examines how such a diagnosis was could not be applied to all the medical phenomena to which physicians put it. His project involves a series of case studies from 1819 to 1850 across the entire Confederation in which various amphibians—lizards, toads, and snakes to name a few—seemed to have entered the patient's body. In these circumstances, hysteria was only one of a range of options—from outright fraud to spontaneous generation—used to explain these occurrences. The focus of this work was the arguments used, as well as the people who used them, to normalize these worrying events.

While preparing her PhD on the concept of contagion in nineteenth-century England, Debolina Dey examined the use of contagion as a metaphor in public debates about the poor, in commonplace books, in legal texts such as the New Poor Law (1834), the Public Health Act (1848), and the Contagious Diseases Acts (1860s), and in literary works such as Dickens’s Bleak House. She argued that for disease to attain its ubiquity in the cultural imagination of Victorian England, it had to operate both as a historical phenomenon and as a literary metaphor that could be appropriated into various other discourses. Here again, a medical category was used to claim the need for normalizations: cleanliness, sanitation, hygiene, education for the poor, and a whole series of measures associated with the urbanization process. Despite predicating ideas of social justice, these texts circulated the category of contagion to exemplify the need for strict morals, civic conduct, and social order as key to the health of the nation.

Conceptual changes in the classification of Alzheimer’s disease formed the center of Lara Keuck's doctoral dissertation and postdoctoral work. In her project, she examined the very beginnings of the making of this medical category and contextualized her analysis within the intellectual environment of the second half of the nineteenth century in imperial Germany, especially with regard to the emerging disciplines of experimental psychology and academic psychiatry. The project focused on interactions between psychiatrists and patients, and their effort to perform and record a distinct clinical picture.

During her residency, Anne Harrington, worked on on the final drafting of a book with the working title The Suffering Mind. This book was the first general history of psychiatry book since 1997. In this book Anne Harrington practiced a style of historical analysis that she calls “history at the boundaries.” By this, she means a way of attending to the historical material that pays particular attention totracking traffic between developments “inside” psychiatry (the institutions, the treatments, the policies, the approaches), and developments that we generally assume to be “outside” it: immigration, slavery, race and racism, modern warfare, consumerism, poverty, crime, family life, religious experience, sexuality, civil rights, drugs, licit and illicit, and more. Conceived this way, the story to be told here is big. Not at all of just specialist interest, it turns out to be actually one of the important stories of the making of modern life. At least for the past century, it turns out that, when our world changes in some fundamental way, understandings of mental illness and mental health are part of the story. The great advantage of writing the history of psychiatry in this way is that it helps one to better understand not just what psychiatry does and believes at any one time, but also what it means for people at the time, and where it fits into the larger world.