The project investigates if and to what extent antique natural science continued to have an impact after the seventeenth century, despite the rise of a new approach that explicitly contradicted the antique tradition. The central research questions are:

- If and to what extent did classical physics and analytical mechanics supersede the auctoritas of antique knowledge of nature?

- How did the mathematization of Newtonian mechanics in the eighteenth century differ from Newton’s original conception of mechanics in the Principia?

The project sets this development into the context of a famous debate about the superiority of ancient versus modern culture, known as the querelle des anciens et des modernes. This debate also found expression in conflicting positions about the developing mathematical methods of natural philosophy. Isaac Newton explicitly referred to the authority of Euclidean geometry as a justification for the conservative form of the proofs in his Principia mathematica, where he avoided the use of analytic geometry and infinitesimal calculus, the central innovations of seventeenth-century mathematics, as much as possible. Rather, he modeled his proofs, just as the overall structure of the treatise, as closely as possible on Euclid’s geometry. A century later, however, Joseph-Louis Lagrange announced in the introduction to his Mécanique analytique that no geometrical diagrams would be found there and that Newtonian mechanics was presented exclusively in the form of analytic equations. The project analyzed the relationship of this radical change in the theoretical methodology of mechanics to the actors’ ideas about ancient science and its authority. It also treated the consequent development of a conception of ancient science as distinct from modern science and the relation of this conception to a history of science in our contemporary sense.

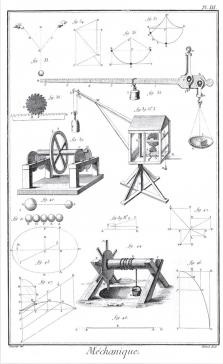

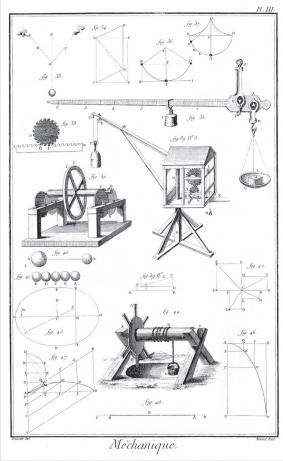

The plate on mechanics from the Encyclopédie edited by Denis Diderot and Jean Le Rond d’Alembert relates, technological problems to the new methods of analytics, representing the emerging field of analytical mechanics.