Cropscapes

-

Beerscapes

Beerscapes

contributed by Francesca BrayBeers and Their Worlds

Though most of us equate beer with its European variant, barley-beer, almost every human society produces some beer-like drink, a mildly alcoholic liquid brewed from locally available starches, one essential product of the local cropscape. Sometimes beer is made from the main food-staple: manioc in Amazonia, for instance. Or the beer ingredient may come from another plant, like Mexican pulque made from agave cactus. Animal sugars can also be used: honey for mead, or milk for koumiss. Whatever the raw materials, beers share two great virtues: they are safer to drink than most untreated water-sources, and they lubricate social intercourse, hence their near-universal popularity.

Tray of Western barley beers, picture released by author

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aufse%C3%9F_Bier.JPG

Today the big Western and Japanese beer companies have gone global, successfully persuading people around the world that European-style barley-beer is the drink of modern, cosmopolitan citizens. Yet many local beer-scapes have survived in the face of this corporate onslaught precisely because they are local, not global.

Amazonia: The Jaguar’s Beer-Garden

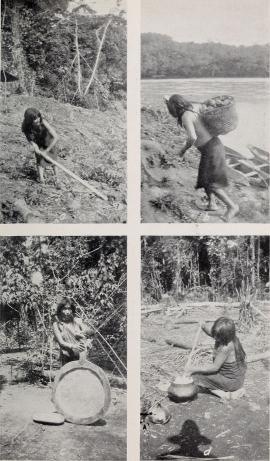

The Napo Runa of Ecuador say that “manioc beer is the life of Runa people.” Runa women grow, prepare and cook manioc for food; more importantly still, they brew it (in pots referred to as wombs) into asua, manioc beer. Men fish and hunt for game; the meat they bring back is prepared and cooked by women and thus converted into food, human sustenance. Runa men passionately desire asua, which women bestow upon them in erotically charged presentations when they return from the hunt. Women as passionately desire meat. Thus every action, every meal becomes a celebration of gender complementarity. Asua itself is celebrated as the essence and breath of Runa being. Meat and asua circulate constantly between related households, or (in marriage feasts) between Runa groups often living many miles apart, binding together the local community and the whole Runa people. Asua embodies Runa ideals of gender, labor and desire, expressing a cosmology in which plants and animals share human perspectives albeit materialized in different forms of substances: jaguars crave blood in the same way that humans crave beer.

Amazonian women preparing manioc beer; Smithsonian, no restrictions

Attribution: Smithsonian Institution. Bureau of American Ethnology -

A focus on beer highlights the role of the Amazonian cropscape in producing particular kinds of human body and social-spiritual identity, as well as moral-material relationships, here conceived of not as restricted to humans but also including animals and plants, the home, the village, the garden and the forest as well as the cosmos.

Asua beer is so closely bound to Runa identity and being that it does not travel. On the contrary, with the penetration of colonial and then global forces asua and many other “native beers” have become symbols of cultural identity and resistance, for instance the post-NAFTA revival of Mexican maize-beers, tejate (“the drink of the gods”), celebrated for its pre-Columbian roots and savors. Probably the most famous celebration of “beer as us” is the song Umqombothi (African beer) by Yvonne Chaka Chaka.

Bibliography:

de Castro, Eduardo Batalha Viveiros. "Exchanging perspectives: the transformation of objects into subjects in Amerindian ontologies." Common knowledge 10.3 (2004): 463–484.

Soleri, D, DA Cleveland, F Aragón Cuevas, “Food globalization and local diversity: the case of tejate.” Current Anthropology 49, 2 (2008): 281–190.

Uzendoski, Michael A. "Manioc beer and meat: value, reproduction and cosmic substance among the Napo Runa of the Ecuadorian Amazon." Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 10.4 (2004): 883–902.

-

Teascapes

TeascapesTeascapes: Transfer and Transformations

In an important case of South-to-South transfer, tea (as a crop) was introduced into India, starting the 1830s from China. It was to be found later that tea plant as such was not new to India as a variant of it was found in Assam. But tea plants and most importantly the culture and knowhow of tea entered India from China in a big way in the 1830s. Tea would never be the same again as this transfer entailed considerable transformations on diverse fronts—the scale of cultivation, nature of ownership, mobilization of labor; methods of processing, marketing techniques, social reach, etc.

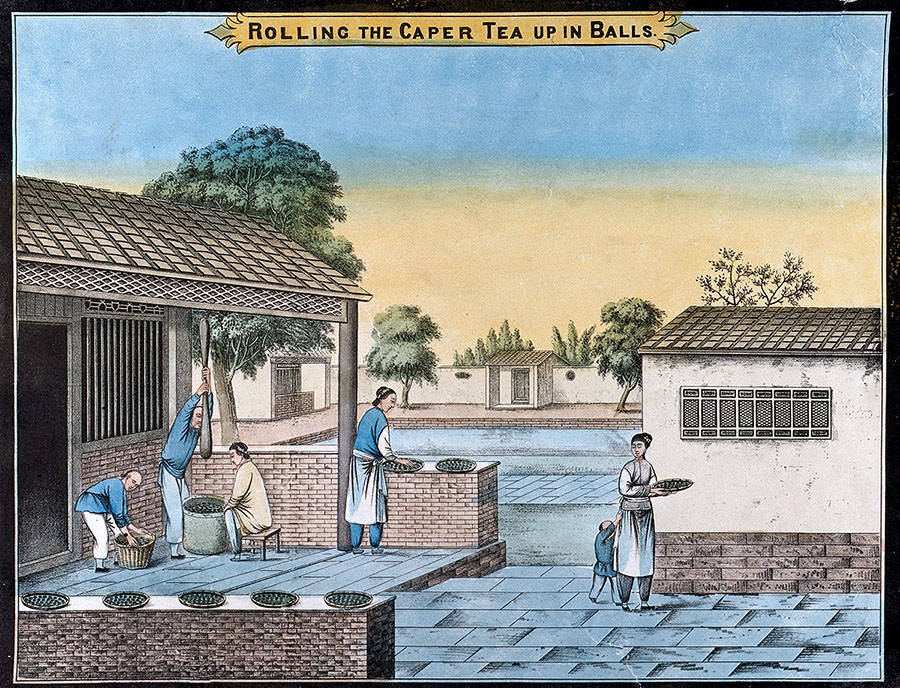

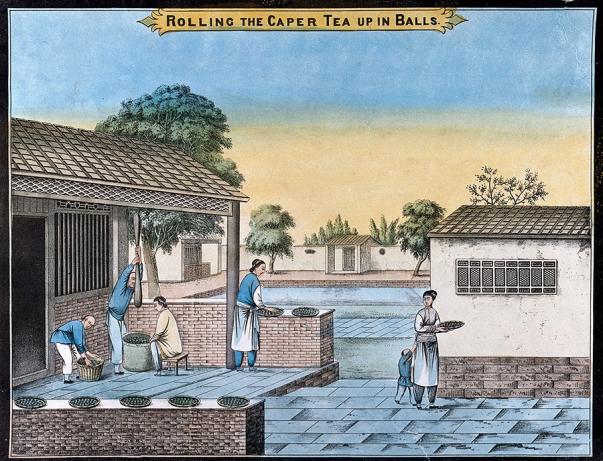

In China, tea was grown more like a household agricultural crop, cultivated on a small scale by independent peasant farmers except for a brief interlude in the eleventh century, under the Northern Song dynasty, when tea was a state monopoly and the government set up centrally-managed tea estates in the parts of Sichuan and Fujian. The plucking and processing was by and large manual.

A tea plantation in China: Workers roll the caper tea into balls. Coloured lithograph.

Courtesy : Wellcome Trust Collection UK

When the British began to grow tea in colonial India, the cropscape that developed was radically different from the Chinese scenario. The cultivation of tea as a commercial crop entailed the creation of new places, as the plantations radically altered the virgin forests they replaced. The wild forests had to be "tamed" and brought to "fruitful" use. Through this work of civilizing the place, jungles were transformed into (tea) "gardens." The reconfigured cropscape involved "civilizing" not only the place, but also a local variant of "wild tea." Even as the EIC made efforts to transfer tea from China, a local variety of tea was discovered in Assam, in the north-eastern part of India. The variant had to be brought from the periphery of Assam to the new cropscape; from its "wilderness" to its new "garden."

The factors that prompted and facilitated this imagination and creation of new places are diverse. Tea as commodity was an important element of trade for the East India Company (EIC) since the early seventeenth century and EIC had a monopoly on that trade. However in 1833, the British parliament abolished the Company's monopoly over tea trade. This set the Company on the path of exploring possibilities of producing tea within India and setting India up as a new export springboard. Also with the availability of capital it could experiment with hitherto unexplored possibilities, including a strong ideal of mechanization, which took several decades to take full shape but was in complete contrast to the smallholder teascape. Most crucial in enabling these new teascapes was the colonial state, which facilitated the meeting of capital and crop through land allocation and help in transferring experimental farms. The emerging cropscape also included managing agents in Calcutta who mediated between British capital and the tea companies in Assam and the rest of India, and between the product and the consumer market.

Moving tea meant not only physical, botanical, and ecological changes, but also new social patterns and relationships in the new place. This in turn introduced another element of mobility: the bringing of families from the plains or far-off locations, to the new tea habitats. Thus the place was a new habitat both for the plant as well as for the people around the plant, whether owners, managers or laborers. The new cropscape was held together by a hierarchical system of management running from the white British manager to the indigenous laborer. The hierarchy was also reinforced in space, from the high-perched luxurious bungalow of the white manager to the ramshackle huts of the "native coolie lines." The new cropscape thus had its unique racial/spatial markings.

But this ordering went beyond just the human to encompass the realm of animals too and brought about significant reconfiguration of human-animal relations. Apart from uprooting and unsettling the fauna, teascapes involved other entanglements with animals. For instance, a recurring feature was the incidence of attacks by leopards and boars—entailing constant tension and vulnerability. These instances can be read as a desire on the part of the fauna to re-assert their own right to the place, and to interrogate or resist the new cropscape imposed on them by erasure of elements of their erstwhile habitat. In another example, waterlogging in the tea estates’ draining trenches introduced mosquitoes as an important element of the Assam cropscape.

Photo by JBL (in a tea garden in Assam). The trenches by the side of the tea-plant bed collect excess water, but also turn into breeding grounds for mosquitoes.

Malaria and its fatal consequences introduced a further element of ferment and cruel dynamics in a place where labour forces perished and were constantly and with great difficulty replenished. The subsequent discovery of connections between mosquitoes and malaria brought further dimensions to the place-making in terms of the introduction of newer elements, such as the cinchona grown to combat the malaria menace. The new place was thus rendered a constant war-zone, precisely because of the very nature of the place-making mosquitoes against men; cinchona against mosquitoes; animals against men (and vice versa) and finally men against men (pathetic laborers trying to escape the horrors - malarial and managerial - of the new place and the management cruelly restraining them).

Looking beyond Assam, there are actually a range of teascapes across India. After tea’s successful introduction into Assam as a plantation crop, in yet another dimension of internal mobility, tea was trialed and successfully expanded to several other parts of India like Darjeeling (also in the eastern part of India), Kangra (in the North) and Nilgiris, Wayanad and Munnar (in the South). Each of these regions had different terrains and features, including elevation, climate, rainfall etc. Each bioscape thus produced corresponding variations. Mountain trains for instance formed an important part of the reconfigurations of cropscapes in hilly Darjeeling and Munnar plantations.

High Range Light Railway (pre-1924) Munnar, Munnar Tea Museum, Photo by JBL.

A hydro-electric power project, which could not be part of the Assam tea cropscape, formed an important part of the new cropscape of mountainous Munnar. This had other implications such as new options for energy and different ways in which resources could be allocated and things could be done. Also the creation of tea estates in hilly areas coincided with another variant of place-making: the establishment of hill stations (not seen in the Assam cropscape). The love and longing for the temperate homeland and its flora could be experienced to some extent in the cool climes of the hill stations. On the sidelines of the tea plantations, within the managerial bungalows, one could recreate the floral beauties and hedges that the white planters missed and longed for.

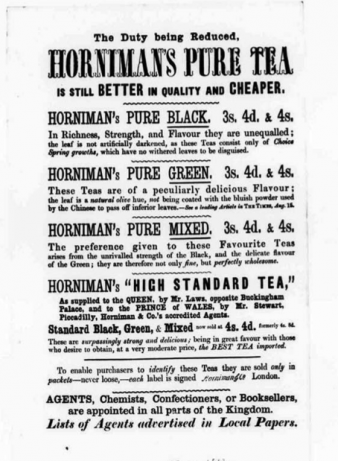

While all these places produced teas, the teas had different characters. The place defined the taste, influenced the demand and decided the right kind of market. The Darjeeling tea for instance was renowned for aroma while many of the southern Indian varieties were sought after for their strength. In course of time, the places also gave their names as Geographical Indicators ('Darjeeling Tea' for example) creating niche markets for them in the global trade of commodities. This is another remarkable exposition of how a crop makes the place in the sense of giving it a whole new identity. Tea gives an identity to its new place and gets another itself in turn. Again this identity is not in terms of its particular physical location alone but enunciated constantly by its inhabiting and spreading in the imaginations/mental images of men, and advertisement campaigns across different places - Darjeeling, the rest of India, London and the world.

Such entanglements (with other and far-off places) were an important feature of the tea cropscape. The plantation model, the technologies of processing and marketing large Assam-bush leaves into strong black teas to be drunk with milk and sugar, spread steadily throughout the spaces, races and classes of the British Empire.

Upwardly-mobile young men from England and Scotland went out to manage tea-estates established wherever the ecology was deemed suitable, even beyond India—to Ceylon and then East Africa.

From a luxury for the rich, tea become the everyday beverage of the middle and then the working classes, first in the British Isles, then across the white-settler colonies and eventually among “natives” in India and other British colonies. Also, tea itself passed through several different places in its journey from a crop to a commodity. Unlike many other plantation crops like sugar or cotton, the processing in the case of tea happens very close to the growing field - within the very estate itself or in the nearest factory in the area. On the other hand, after it leaves the factory, and before it reaches its customers, it passes through hundreds to thousands of miles with much of its destiny as a commodity being decided at auction centers, which can be 100 miles from the tea field or 10,000. Blending centers are other important places which add meaning and value to the tea in transit. These distant places—some of which do not grow/produce an ounce of tea themselves—determine the fate of the tea as eventual commodity, as much as the place of its growth and processing. Hence, in spite of the remoteness of the self-contained tea garden, the fate of tea was shaped by multiple other places and processes.

From: The Modern Review January 1942.

Thus a combination of socio-cultural zeal, new economic ambitions, new scientific/botanical studies and experiments, new means of acquiring labor, new managerial systems, financial arrangements (the managing agency system), mechanical innovations and social arrangements—all serving as multiple and inter-related constitutive factors that brought the cropscape into being and shaped the place, while the crop too was altered by the place. In the process, the cropscape acquired stability—a stability aligned to the desire and ambition of the colonial state and corporate interest.

-

Tobaccoscapes

TobaccoscapesTobacco Oscillations: Changing Size on the Spot

Cropscapes offer new perspectives on the size of tobacco cultivation units over the centuries. In other chapters we have analyzed the life-cycle flexibility of the tobacco plant—that is is a perennial grown commercially as an annual. We have also spoken of its geographical mobility. Here we focus on a single location, the Virginia-Carolina border where tobacco has been produced consistently from at least the 1600s to the 2000s. By keeping place constant we can trace oscillations in the size of the farm, or cultivation unit, that spooled out across three centuries. These size oscillations show how non-plant elements in the cropscape—legal and technological changes—interacted in the reconfiguration of both spatial size and labor organization. Changes in the size of tobacco farms in a single location demonstrate a non-linear history that moves from small to large to small to large again under different legal and technological frameworks. Recognizing the oscillatory nature of the tobacco farms demonstrates that cropscapes need not move to change, revealing and reconfiguring elements in the classic tobacco cropscape.

When the first shipment of tobacco to England brought a high price in 1617, colonial settlers “stopped bowling in the streets and planted tobacco in them.” For the next century, English colonists cultivated tobacco on both small farms and large plantations. Virginia Company policies and the House of Burgesses (the colonial legislature), however, favored planters with more resources. Stint laws that were intended to limit supplies and thereby raise prices limited the number of tobacco plants per person, while headrights granted land to those who paid the passage of bound laborers. These provisions resulted in early engrossment of the best land in the hands of planters with the money to import labor. The laws and their effects created grand plantations along the Chesapeake waterways—some of the oldest fortunes in British America. Nonetheless the crop was famous for the opportunities it provided even to smaller-scale and poorer producers, and a medley of small and large farms co-existed up to the 1720s.

At that point, with the introduction of inspection laws in the 1720s that approved for export only high-quality tobacco, and forbade sales of the plant’s second growths, economic historians identify a “steady upward drift” in the size of tobacco farms and slave labor forces. The tendency was there already: slaves already existed in the region, of course, and laws after 1660 demonstrated emerging distinctions between slaves and servants. But the changing legal landscape of the 1720s decisively favored planters who could command large numbers of workers at crucial harvest points, disadvantaging smallholders. This second phase in the oscillation of tobacco farm-size in Virginia created a cropscape of large cultivation units that employed and facilitated a patriarchal ideology characteristic of the plantation system. As production units, these plantations mirrored the manors of medieval Europe, with planters viewing the entire household as familial, organized in webs of mutual responsibility and obligation. “Thirty of my family are down with the smallpox,” a planter wrote to a merchant in the 1820s-30s, as if his slaves were his children. Thus the colonial inspection laws combined with provisions granting land to planters who had labor, and the laws governing and taxonomizing those laborers, all contributed to the changing size of the tobacco cropscape in eighteenth-century British America.

Federal law, in the form of the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, initiated a third phase of oscillation as the size of tobacco farms shrunk after the Civil War. Though landownership mostly remained concentrated in the hands of the former slave-masters, the scale of cultivation dropped as sharecropping re-organized what had been slave labor. Not only the organization of production but the nature of cropping practices changed in consequence. Sharecropping relied on annual credit: farm families waited for harvest for their pay and owed landlords and storekeepers for rent and food and seeds and fertilizer. Each group provided credit to the others, with all bills due at the end of the year. To keep all parties afloat, harvest and curing methods emerged that allowed a new annual production cycle of several harvests. Instead of chopping down the whole plant, as had been done for centuries, a new system emerged, organized around plucking individual leaves. Harvesting individual leaves, then going through the fields again to pluck another set of leaves, meant barns could be filled for curing and then cleared out for another round. Farmers used extended-family labor systems to adopt the new techniques. “We barned Uncle Montgomery on Monday. Saturday was Uncle Dewey’s day. All of us worked together. No one would barn Wednesday or Thursday . . . because that would mean adjusting the fire on Sundays and, well, this is the South.” Thus the nuclear family on the small farm was one part of a larger web of labor arrangements and technical strategies needed to make the whole cropscape work in its new configuration.

Another new element in the post-emancipation system was chemical fertilizer. Fertilizers allowed small postbellum farmers to plant on poor, sandy soils, producing a brighter, milder tobacco. Here too the state aided the adoption of new technology, new elements of the cropscape—not through legislation but by providing chemists to test fertilizer brands and to adjudicate disputes over quality. These chemists worked at the new North Carolina Agricultural and Mechanical College, one of the land-grant colleges established after the passage of the Morrill Act in 1862, which also contributed instructions in the harvesting and curing methods that reliably made tobacco bright, yellow, and mild enough to inhale. Bright tobaccos turned tobacco manufacturing into Big Business in the last decades of the nineteenth century, as tastes shifted towards smoking. Small firms that had previously produced mostly chewing tobacco were absorbed by a large-scale consolidated producer of cigarettes, the infamous combination (some, imprecisely, call it a monopoly) known as the American Tobacco Company. Big Tobacco bought tobacco from small farmers in warehouses, with auctioneers to help farmers sell and manufacturers or middlemen buy a small pile of leaf in a basket—just a hundred pounds or so at a time.

After the US Civil War, tobacco farms along the border of Virginia and North Carolina shrunk back to the small size that had disappeared with the rise of antebellum plantations. The small farms used larger labor forces to remain viable, and extended families rotated their labor across the farms of all family members for harvest and curing. Image courtesy of the North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Thus large-scale tobacco plantations from the colonial and ante-bellum periods became small farms under new post-bellum regulatory and labor systems. In the 1930s, New Deal policy locked farm size into its small space for a few decades more. Its federal support for agricultural prices limited how much each farmer could sell and therefore capped farm sizes. However, in the last three decades of the twentieth century, the size of cultivation units grew once again, this time to justify investment in new harvesting machines. The post-bellum method of harvest, the plucking of individual leaves, became embodied in a machine patented in 1971. Purchasing and using such a machine was only viable for farmers who had larger plots to work than the New Deal allotments permitted. Earlier legal changes had paved the way for mechanization: in 1961 and 1962, new laws allowed farmers to sell or lease their tobacco allotments to other farmers within their county, which allowed farms to grow large once again.

The new larger farms were the fourth phase of size oscillation in the tobacco farms of the Virginia-Carolina region. Once again this transformation was catalyzed by interlocking changes in law and technology: the softening of the limits on farm size that had emerged in the postbellum South, hardened by New Deal policies in the 1930s, and the harvesting machine that made only larger farms profitable. Other sociotechnological changes ensued from this single invention: the move to bulk curing eliminated the labor of women who had looped individual leaves onto sticks for men to hang in the curing barns. As the system shifted along with the increasing farm size, the labor arrangements of nuclear and extended families also changed, yet the mechanization of harvest and curing was sold to farmers as a return to family farming -- a way to be rid of sharecroppers and wage workers. The expertise of the USDA and the North Carolina State University contributed to the development and marketing of the machines, and the harvesting machine patent was assigned immediately to R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, indicating the likely support of the biggest buyer of the region’s tobacco for the mechanization of cultivation and its associated growth in farm size.

The size of tobacco cropscape changed repeatedly on the Virginia-Carolina border as a result of larger trends in U.S. history. From a crop that suited small and large farmers alike, in the eighteenth century tobacco became a plantation crop that only rewarded large-scale producers and that used slave labor. After the Civil War, emancipation of the slaves and changing credit arrangements shrank the scale of tobacco production to small sharecropping farms, and in the 1930s, the small scale of production became law as allotments limited how much each farm could sell. This scale of production expanded once again when government permitted the allotments to be sold or leased, creating consolidated farms that repaid mechanization in ways that smaller crops could not. While the location of production stayed the same, the cropscape’s inputs changed dramatically with each oscillation phase. Fertilizer helped make farms small post-bellum; in the 1970s farms grew to accommodate the harvesting machine, which required regular infusions of gasoline if it were to do its labor-saving work. Mechanizing the tobacco harvest required gasoline. This demand linked tobacco farms to new markets. It also solidified cultivators’ relationships to older ones--the corporations that bought their produce.

Tobacco’s oscillations are a simple history that unveils how many different elements play a role in size, and it complicates the perceived causative relations among them. The plant did not dictate the farm size, but the entire cropscape incorporated and caused and was caused by changing sizes. Likewise, the mosaic of production systems for coffee in Ethiopia are pure history.

-

Waterscapes

WaterscapesCultivating Water

Water is an essential component of all cropscapes. Crops need water and so too do humans and animals; water slakes the thirst of living creatures, and human populations also use water to keep clean, and for almost every kind of processing and manufacture, from cooking and pot-making to nuclear cooling towers. In fact we can usefully think of water as a crop, carefully planted, tended and harvested by individual farmers, local communities or states.

Techniques for managing water range from setting up a barrel to collect rain from the roof, or matching planting and harvesting to the monsoon, to the building of grandiose irrigation systems like Angkor Wat or Aswan. Here are two typical water-cropping systems, selected among dozens.

Horse-hoeing Husbandry

"Are you able to make low, wet land fruitful? Are you able to conserve dry soils and temper them with damp? Can you purify your soils, making ditches to wash them clean? Can you ensure that your millet heads will be rounded and the husks thin, that the grains will be numerous and plump so that food is plentiful? How may you do all this? By the fundamental principles of tillage." (Annals of Lü Buwei, ca. 239 BCE)

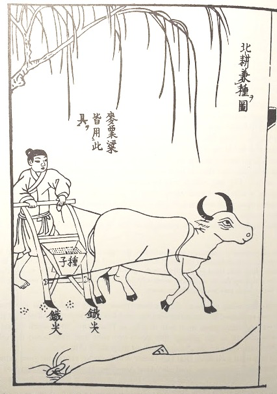

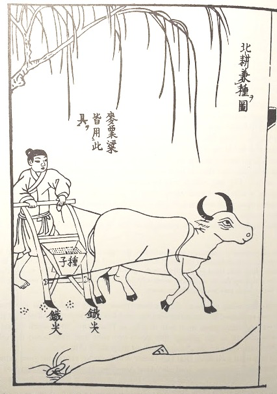

From as early as 300 BCE and through into the modern era, farmers in North China used a specialized repertory of ploughs, harrows, rollers and hoes to capture moisture from winter frosts and scarce summer rains, ridging and draining damp and heavy soils, and creating a crumbly mulch on the surface of dry soils to prevent evaporation. Seeds were planted in rows by drill, maximizing the moisture for each plant and facilitating weeding. Green manures were ploughed in before sowing grain to fertilize and retain moisture in the soil. In eighteenth-century England, apparently independently of any knowledge of Chinese farming techniques, very similar farm implements and principles of tillage were devised by Jethro Tull, author of The Horse-Hoeing Husbandry, and other pioneers of the English Agricultural Revolution. In North China "conserving dry soils and tempering them with damp" was the primary goal, but English farmers were more concerned with "making low, wet land fruitful."

Chinese farmer using seed-drill; 1637 illustration (Tiangong kaiwu)

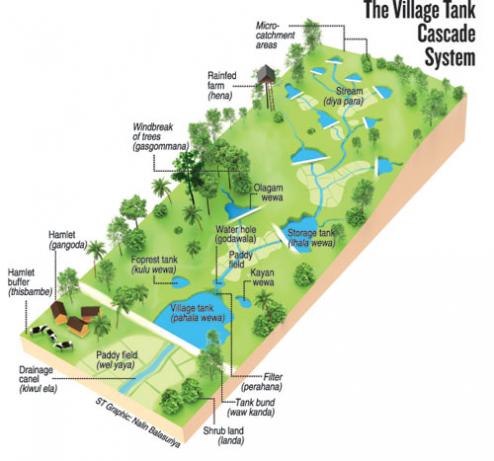

Tank Irrigation

In monsoon Asia irrigation tanks have been used for over two millennia to capture water from rain or streams so that it can be released in controlled fashion as and when needed. Some tanks were just a few meters across, built by individual farmers. Every spring the farmers dredged and repaired them. A Chinese text of 1149 advises planting mulberry trees around these small tanks: the roots strengthened the banks, the boughs offered precious summer shade to grazing water-buffalo and the leaves were harvested to feed silkworms. The trees also served as buffers, preventing both excessive evaporation and overspills after heavy storms.

Tanks range in size from small to huge. In the dry zone of Northern Sri Lanka networks of huge and small irrigation tanks were constructed under royal order as long ago as 450 CE; today 320 ancient large dams, and 12,000 ancient small dams survive, along with many thousands constructed since. In what is known as the Cascade Tank System, multiple tanks are connected in cascades leading down from the forested hills to the paddy fields below the village. Forest tanks, at the head of the system, not only capture rainwater for the main village tank but also provide water-holes for wild animals, reducing the risk that they will come down to the village and damage crops. Intermediate tanks trap sediments and reduce salinity, and are used to water seasonal crops grown in gardens above the village. The main village tank stores water for human needs and for rice-growing. With civil strife and rural change many of these ancient cascades had become neglected. This affected not only crop yields, but also local drinking supplies, soil erosion, vegetation patterns and biosystems more generally. Partnered by international conservation organizations, the Sri Lankan government has recently embarked on restoration programs for deteriorated cascade systems.