Source: Sam McGhee, Unsplash.com

But researchers trying to utilize these sources currently face serious challenges. The biggest problem with this corpus is accessibility. For starters, it is impossible to search across all these collections. These interviews are to be found in various media across different institutions with heterogeneous metadata and privacy restrictions. To find out what oral histories are available, the researcher must trawl across different sites in an unsystematic and time-consuming manner, meaning that these valuable resources are often neglected by the scholarly community. There are also more fundamental restrictions that make access more difficult, such as legal restrictions on who can hold, view, and cite these highly personal documents. And finally, there is often a risk that these digital resources will become unavailable as project websites cease to be maintained. But the main problem facing researchers today is a practical one of simply not knowing what is out there. In order to help make this corpus a common resource for scholars across the broad field of the medical humanities, we are developing an open-source website infrastructure for the networking of oral history repositories. The Commoning Biomedicine project is a digital humanities collaboration between the Research Group “Practices of Validation in the Biomedical Sciences,” led by Lara Keuck, and the Research IT team at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science that aims at making oral histories of biomedicine a common knowledge resource.

Commoning Knowledge Resources: Collaboration, Conversations, and Code

What is commoning? The term stems from the history of struggles over land enclosures in early modern England but has more recently been adopted to talk about sustainable ways of administering environmental and digital resources. We take it to define a commitment to using open-source digital tools to establish sustainable common knowledge resources. Within this framework commoning is divided into what we call the 3 Cs: collaboration, conversations, and code. In order to make oral history collections more accessible in a sustainable way, we cannot simply build search tools, but must foster greater Collaboration between oral historians and archivists. For example, we have established a working collaboration with the Science History Institute in Philadelphia, which hosts one of the largest online oral history collections related to science and medicine in the world. We host regular workshops called Conversations to build connections among researchers who use digital oral histories and strengthen the scholarly community. But the central focus of our work remains developing open-source Code for networking online collections of knowledge resources.

Click image to see in full.

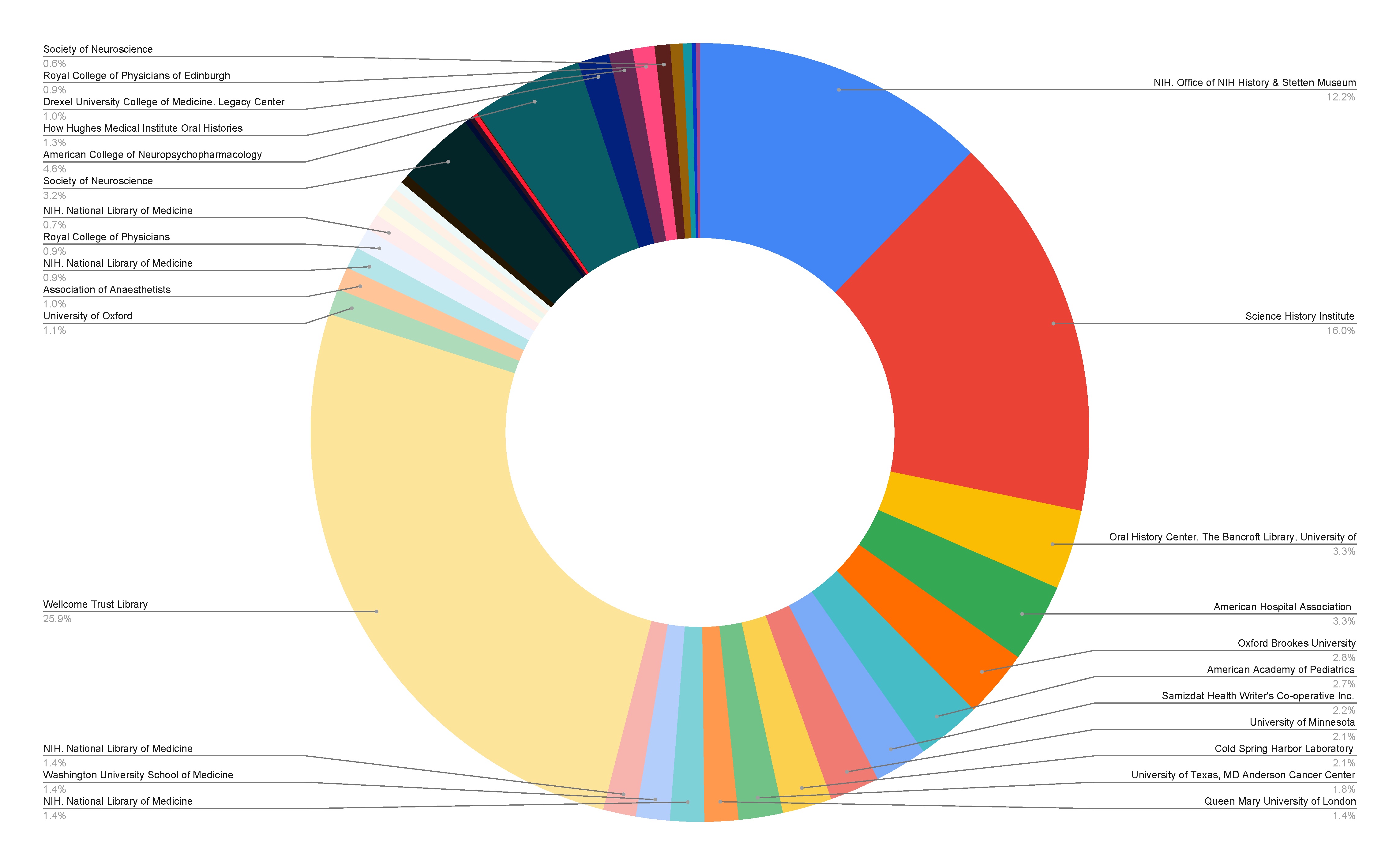

Image: Chart showing spread of oral history collections relating to biomedicine across different institutions, resulting from our 2022 survey of collections. Credit: Alfred Freeborn.

Big Data Problems without the Big Data

Networking decentralized collections of oral histories poses many challenges often confronted in Big Data projects: database federation and integration, schema and ontology formalization, data sanitization and normalization, scaling, and security. In a less technical idiom, this means identifying information from various separate databases, integrating them together without centralizing the original data in a single database, and standardizing the data so that a user can search across these different databases. Early on we collated a comprehensive list of repositories containing oral histories that relate to biomedicine (both online and offline) as well as deploying, testing, and auditing a variety of web frameworks for oral histories currently in use.

The survey revealed a problem common to many digital humanities projects: insufficient data. The current body of biomedical oral histories is actually rather small relative to the volume of information typical to Big Data projects. In addition, oral history collections often contain little to no metadata—such as information about the date and location of the interview or the names of those involved. The aforementioned Big Data challenges are compounded by limited resources and poor-quality metadata. This shortcoming can be summarized as “Big Data problems without the Big Data.” It became clear that a unique suite of new and existing technologies needed to be implemented in order to create a robust, flexible, and scalable system.

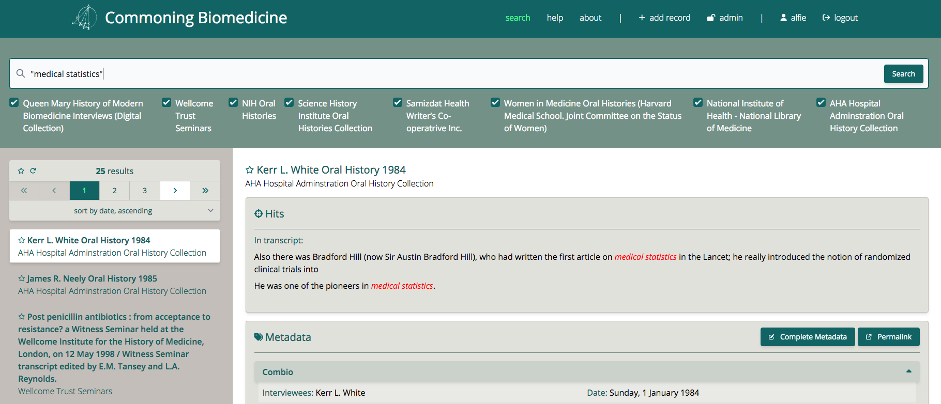

The platform we have developed is designed according to three core principles: ease of use, malleability, and reuse. The user is presented with a search engine that aims to be familiar and intuitive. It allows users to toggle through collections and quickly find the relevant parts of a transcript. By reuse, we mean the ability to use the data beyond the initial search interface that we have developed. The whole system is designed so that microsites using our data can easily be developed on top of our system. Along with others at the MPIWG, we have been quick to utilize the power of Large Language Models[1] to automate and refine our metadata extraction process with some promising early results.

Image: Screenshot of the ComBio platform Beta version.

After launching a Beta version of the platform in July 2023, we have been working hard to add more and more collections to the network and improve the quality of metadata. Ultimately, our methodologies can be generalized in order to make digital platforms for oral histories beyond the topic history of biomedicine more useful and accessible for researchers. The ComBio Project, however, will help researchers write better histories of biomedicine by making vital knowledge resources accessible. But on another and perhaps more fundamental level, it presents a form of scholarly cooperation in the digital humanities that can help transform how we produce and preserve knowledge for the common good.

Image: Film stills from the ACNP Oral History Archives at UCLA.

[1] A large language model can be understood as a computer program that has been trained on a massive amount of written information from various sources. As a result, this program can understand and generate language and perform various language-based tasks, such as translation, summarization, and text generation.