May 12, 2022

Scientific Questions Then and Now: Space

- 15:30 to 20:00

- Lecture

- Max Planck Research Group (Premodern Sciences)Max Planck Research Group (Final Theory Program)

- Several Speakers

- Dennis Lehmkuhl

- Christoph Horn

- Christoph Helmig

- Daniele Oriti

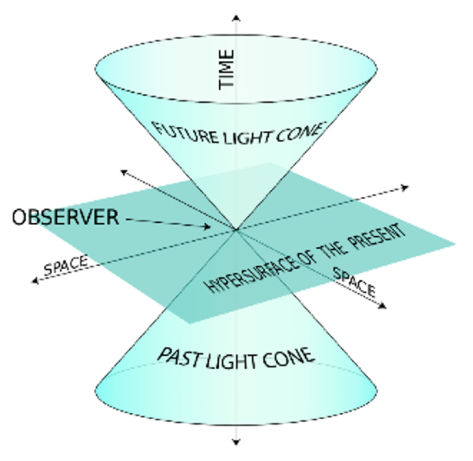

Milne Model. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Abstracts

Contact and Registration

The Lecture Series is open to all interested. If you would like to join a session please contact Anina Woischnig (awoischnig@mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de).

About This Series

How are scientific questions posed and answered by scientists, from premodern times until today? Despite radical changes in world views, the apparent persistence of certain recurrent questions in the history of science is striking: examples of such questions include “Where does the world come from?,” “What is it made of?,” “What is life?," “What is consciousness?,” or “Is the world knowable?”

Our speakers’ series “Scientific Questions Then and Now” seeks to understand the extent to which such recurrent questions have in fact remained “the same.” One key goal of this series will therefore be to determine whether there is, or is not, any core notion of science that remains constant from premodern times to the present, a core notion that would allow for meaningful discussion and communication among representatives of different historic traditions of science.

We will bring together contemporary scientists with historians of premodern philosophy, to ask whether some of these recurrent questions may still be relevant to contemporary scientific research and practice.