Nov 3-4, 2022

Experts at Work II: Ability and Authority Working Group Workshop

- Dept. III

- Several Speakers

- Daniel Patrick Morgan

- Ying Zhang

- Joseph S. C. Lam

- Yiwen Li

- Qiao Yang

- Elke Papelitzky

- Sarah Schneewind

- Morris Rossabi

This is a follow-up workshop of the “Experts at Work I” that took place in June 2021. The workshop focuses on communities of experts in imperial China, foregrounding the experts who have been neglected, or marginalized, by Chinese elite and formal historical writing. Day 1 consists of three invited talks. On Day 2, we discuss pre-circulated papers that the group members have been working on. All the sessions except for the “Internal Discussions” are open to in-person and Zoom participation. If you are interested in participating in one or more of the sessions on Day 2, please read the papers in advance, as we will be discussing the papers without further introduction. Please contact Event Office <event_dept3@mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de> for Zoom link and papers.

Day 1, November 3, 2022

9:30–10:30

An Attempt to Discern Patterns in the Polymathy in the Exact Sciences in Early Imperial China Through Bibliometrics

Daniel Patrick Morgan (Centre national de la recherche scientifique, Centre de recherche sur les civilisations de l’Asie orientale)

The astral sciences in ancient China were conceived as binary, tianwen (lit. ‘heavenly patterns’) and li (lit. ‘sequencing’), that does not map to ‘astronomy’ and ‘astrology’ or any other equivalent; while closely related and placed under the same bibliographic category, the study of celestial and terrestrial mathematics (li vs suan, lit. ‘calculation’) are distinct sub-domains within modern sinology between which cross-overs are rare; scholars such as Howard Goodman and Christopher Cullen have in recent decades revealed the extent to which our historical actors were polymaths rather than specialists; and the recent work of Zhu Yiwen has shown how that polymathy frequently combines such constellations of intellectual pursuits as mathematics, ritual and classical commentary. It has long been my contention that to move past the stage of defining and deconstructing ‘science’, or arguing about the contents of a given actor’s category, we should start over with a statistical analysis of the entire network of actors categories and the density of relations between them to situate people and practices in context. To this end, I will present the results of a tentative attempt to do so using bibliography to detect patterns in fields that, in the aggregate, went along with the mathematical sciences in individual authors’ written output.

10:30–11:00 Coffee Break

11:00–12:00

Making Sense of Confinement: Ming Jailed Officials and Fortune-Telling

Ying Zhang (Ohio State University, American Academy in Berlin)

In the Ming dynasty, officials often went to jail to be investigated for poor job performance, misconduct, and other violations. This legal procedure, for a range of reasons, caused much uncertainty and suffering for officials and their families. I explore how fortune-telling as a technology of life connected legal, religious, and moral knowledge in shaping their understanding and management of imprisonment as a crisis. Specifically, I ask: Who could claim the authority and possess the ability to explain its nature and predict its course? How did such interpretations help justify certain actions and inactions by the prisoners and their families?

12:00–13:00 Lunch

13:00–14:00 Internal Discussion

14:00–15:30

Leading and Supporting Actors in Chinese Music History: Documented Facts, Ideological Claims, and Verifiable Interpretations

Joseph S. C. Lam (University of Michigan)

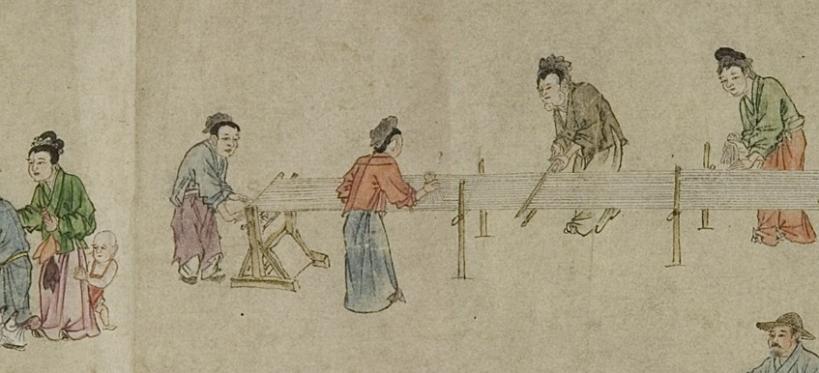

Chinese music history is often told as a dramatic struggle between elite musicians who promoted yayue (civilized and civilizing music) and commoner musicians who practiced suyue (vernacular and/or vulgar music). As registered in court documents and historical-theoretical-musical treatises, yayue defined Chinese music aesthetics, composition, continuities and changes, functions, performance practices, and social-political values. It is no accident that many Chinese hear yayue as the main stream in China's musical past, and historicize its elite practitioners as leading actors in Chinese music history. Refuting such an elitist and linear view, which has been challenged but is still operative, contemporary and socialist Chinese musicologists argue that commoner musicians were the de facto creators of Chinese music, and that elite musicians were merely supporting actors--they merely polished Chinese music genres/expressions with what they had learned from commoner musicians and their suyue. Judging from what is now known about the creative and transmission processes of historical Chinese music, the socialist argument is not without reason. Its credibility, however, suffers from a relative lack of verifiable facts. Biographical, historical, and musical data about historical commoner musicians and their musical abilities and authorities are limited and scattered.

Towards the writing of Chinese music histories that objectively address the roles elite and commoners played in China’s musical past, this talk presents Ming music history as a case study in three parts. The first is a summary of the music chapters of the Mingshi (Ming History), which highlights court music and elite musicians at the expense of commoner ones. The second part is a report on current scholarship about music workers (yuegong), courtesans (geji), and actor-singer-entertainers (paiyou,xizi) in Ming China, analyzing factual and theoretical difficulties in reconstructing and assessing their musical lives and voices. The third part is a musicological reading of two Ming court paintings of state processions that unexpectedly throw light on the musicality of palace soldiers and eunuchs. As such, the paintings underscore not only the fluidity in musical roles Chinese elite and commoners played, but also the practicality of historicizing Chinese music beyond the binary and limiting frame of yayue/elite musicians and suyue/commoner musicians.

Day 2, November 4, 2022

9:00–10:30

Migrant Chinese Artisans in Medieval Japan and Their Networks

Yiwen Li (City University of Hong Kong)

In the late twelfth century, a group of stonemasons migrated from the Chinese coastal city of Ningbo to Japan and participated in reconstructing the prestigious Tōdaiji monastery in Nara. Those migrant stonemasons brought new tools, new carving techniques, and new religious art motifs to Japan. This study focuses on the networks that moved the artisans and their objects of techniques between China and Japan. The migrant artisans were by no means an isolated group—they were connected with sea merchants, Buddhist monks and their patrons and meanwhile cooperated with (and competed with) local artisans. The artisans’ expertise and connections together allowed them to quickly lay down roots in a new society and took part in various local projects.

Who Was a Good Astronomer in the Yuan Court?

Qiao Yang (Max Planck Institute for the History of Science)

Like other dynasties, the Yuan had its heroes of science. And like other periods, these heroes were, and still are, constructed by accounts and biographies, and held up to idealized standards of virtue and ability. This paper critically engages with these accounts and biographies to explore what characterized a good astronomer in the Yuan, who served Mongol rulers, pursued bureaucratic career, and engaged with science at the same time. I argue that answers to these questions varied greatly by the standards of the Chinese bureaucracy, the Mongol rulers, and of the astronomer himself. Moreover, the standards set by each of the three players were not innocent of contradictions.

10:30–11:00 Coffee break

11:00–12:30

Sailing the Waters of East and Southeast Asia: Ming Navigators and their Tools

Elke Papelitzky (KU Leuven)

In the early modern period, the waters of East and Southeast Asia saw a buzzling maritime trade. To conduct this trade, ships needed competent sailors and navigators to safely travel between ports. Chinese sources from the Ming period name one person to be particularly important: huozhang

Sarah Schneewind (University of California, San Diego, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science)

12:30–13:30 Lunch

13:30–14:00 Internal Discussion

14:00–14:45

Communications and “Communicators” in the Mongol Empire

Morris Rossabi (Columbia University)

I am preparing a series of essays that may (perhaps?) lead to a book on communications and “communicators” in the Mongol Empire. The main question is: how, in tangible terms, did the Mongols actually govern the multi-linguistic territories that they occupied in the thirteenth century. How did they communicate with the local elites, as well as with representatives—envoys, merchants, scientists, entertainers, soldiers, etc.—of foreign lands.

Who served as intermediaries in such conversations? Who and how did they transmit Mongol orders? Did material objects, on occasion, substitute for language in communication? Was there a lingua franca that could facilitate interaction? The conventional wisdom is that Persian served as the lingua franca? A recent article suggests that Turkic, not Persian, was the lingua franca. How many Mongols knew these languages? The number of Arabic, Persian, Turkic, and Chinese loan words in Mongolian attests to the intermingling of the Mongolian language and those of the subject populations.

Many questions, a few answers.

14:45–15:15 Internal Discussion