The ISMI database provides a means to access Islamicate authors, their works, and extant manuscript witnesses in the various fields of the mathematical sciences that include the “pure” mathematical sciences (such as geometry, arithmetic, algebra, and trigonometry) as well as the “mixed” mathematical sciences (including astronomy, optics, music, and mechanics). As present, the database contains entries on persons (authors, annotators, copyists, dedicatees, owners, students, readers, etc.) who span the entire Islamic world and South Asia, beginning in the eighth century and continuing beyond the nineteenth.

The public website for the database was renovated in December 2018, and currently contains information on 2300 works existing in 7000 manuscripts and on 700 persons up to about 751 Hijra/1350 AD. More data will be made available throughout 2019.

The ISMI database allows browsing and searching for authors, titles, and manuscript information using Arabic or Latin script. However, as a research tool, it allows the user to go beyond accessing information normally found in catalogues.

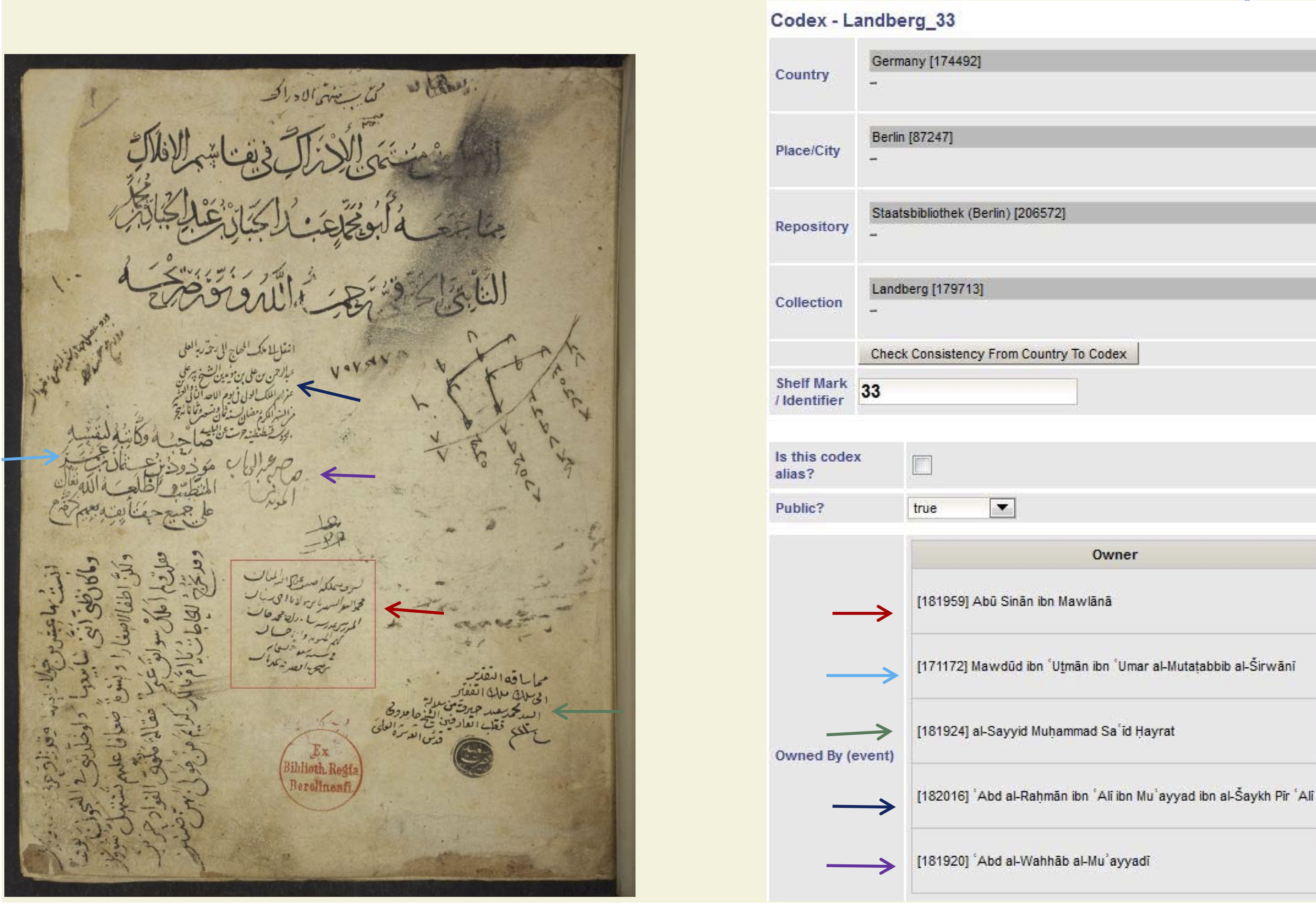

Fig. 1: Ownership notes and study note in the codex Landberg 33, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin.

One special feature of the ISMI database is that it displays commentary chains of a text in the form of links, so you can trace various derivatives of a work over time. In addition, the database includes detail information such as ownership markings and readership notes as seen in Fig. 1, but also incipits (first words of the text), explicits (last words), and colophons (information about text and scribe, often including the place and date of copy). With this information it is possible to identify previously anonymous works, and to show chains of transmission and networks of scholars.

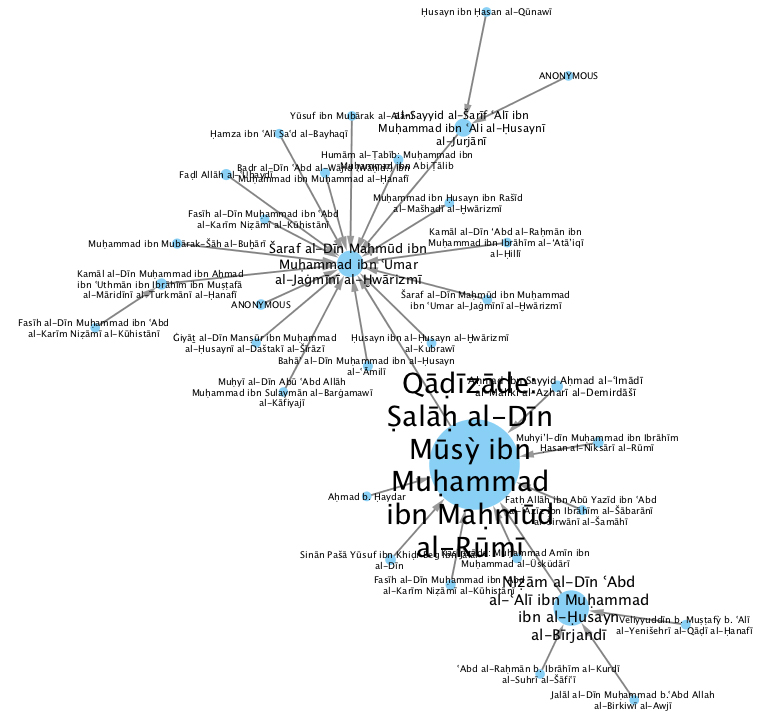

Fig. 2: Experimental visualization of commentary relations around the text al-Mulakhkhaṣ fī al-hayʾa by Maḥmūd al-Jaghmīnī. Shown are authors’ names scaled by number of witnesses in the database.

Fig. 2 is an experimental visualization of the commentary relations of the thirteenth-century text al-Mulakhkhaṣ fī al-hayʾa by Maḥmūd al-Jaghmīnī, using partly non-published data. This work is an introductory text in theoretical Ptolemaic astronomy that was used in teaching, and sparked numerous commentaries, supercommentaries, glosses, and translations for over eight centuries. The visualization shows the network of commentaries in the form of authors’ names scaled by the number of extant copies of these manuscripts in the database. Jaghmīnī is in the upper middle, and we see that Qāḍīzāde al-Rūmī ’s fifteenth-century commentary and Bīrjandī’s super commentary on Qāḍīzāde’s commentary on the lower right have more witnesses than Jaghmīnī’s original text.

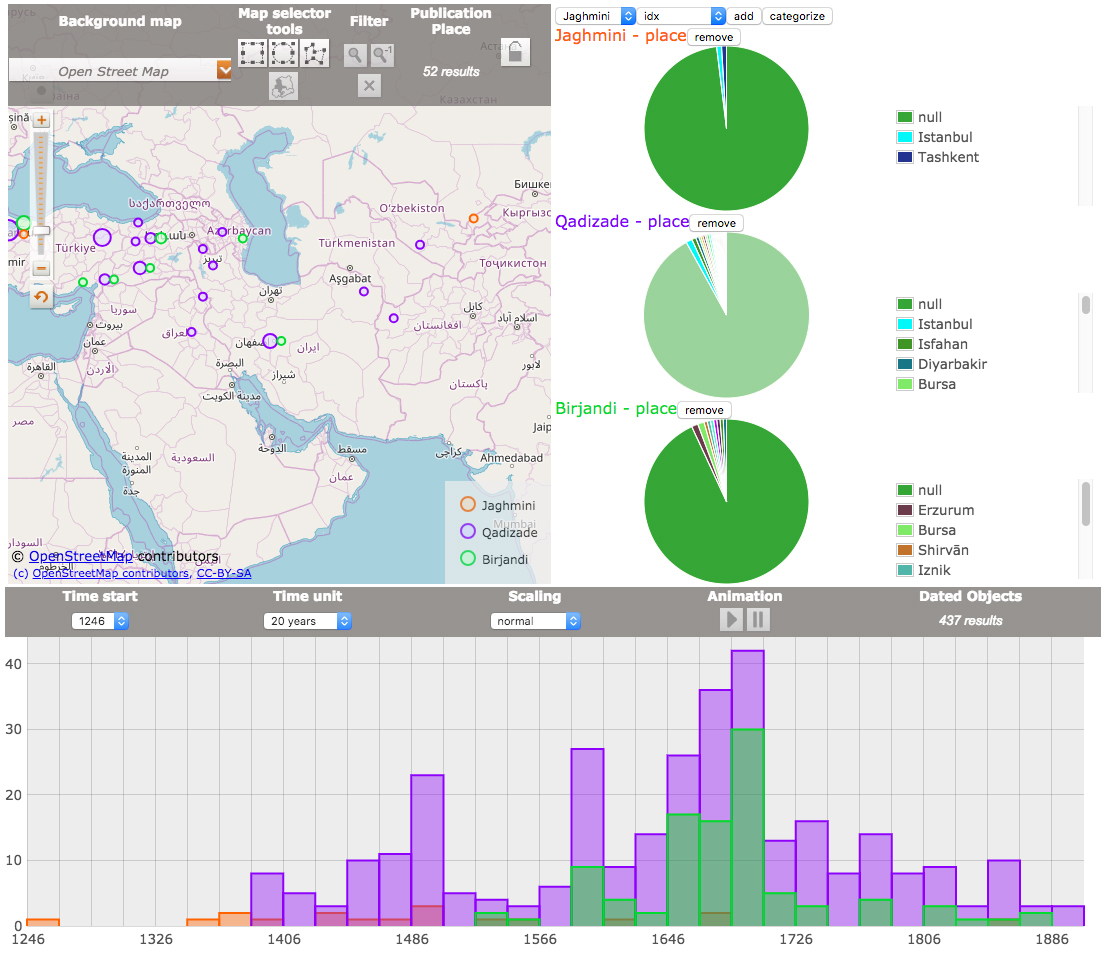

Fig. 3: Experimental visualization of dates and places of manuscripts of Jaghmīnī’s Mulakhkhaṣ source text (orange) and Qāḍīzāde’s (purple) and Bīrjandī’s (green) commentaries using the PlaTiN geobrowser.

Fig. 3 shows a screenshot of another experimental visualization that shows dates and places of witnesses of Jaghmīnī’s Mulakhkhaṣ and Qāḍīzāde’s and Bīrjandī’s commentaries. These are visualizations of the current data in the database. The pie charts in the screenshot show the distribution of places where manuscripts have been copied, with the large green part being entries without a known place, meaning that the place data on the map is limited and not representative. Nevertheless, these visualizations can serve as a starting point for further research, and we can clearly see that this introductory text on theoretical Ptolemaic astronomy was studied, copied, and discussed well into the nineteenth century.

Unlike a printed catalogue, the ISMI database will be constantly updated: its contents will be expanded and corrected and its software has to be regularly maintained as well to remain secure and usable. The custom database software we envisioned ten years ago, and built five years ago, is showing its age. We are currently replacing it with new standard solutions that can be maintained in coming years. This includes the new Drupal-based website and the ongoing transfer of the backend database to the technology of the new Digital Research Infrastructure of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science.

The central focus of the next phase of the ISMI project is to encourage more scholars to engage with the database, and to contribute to the project. So please try ISMI out, and with your feedback we can continue to develop ISMI and thereby showcase our ability to map the intellectual, institutional, religious, and social contexts of Islamic scientific traditions!