“Linguists dig deeper into origins of language”—so ran the title of a 1987 feature in the science section of the New York Times. Just as “paleontologists ponder their fossils” and “archeologists turn over ancient stones,” its author noted, linguists had recently joined in the quest for human origins “seeking ultimately to reconstruct the primordial language, the mother tongue of all humans.”

This article invoked the universal appeal of human prehistory, even though its claims were not entirely true. Indeed, practitioners did “dig deeper” into the evolutionary history of language during the second half of the twentieth century, proposing “long-range” genealogies that reached expansively across space and through time. But very few of them were willing to stake a claim when it came to the ultimate Ursprache—thought to have originated some 50,000 years back. How human language originated (whether this had happened once or several times); how early language was structured and used; and how it diffused and diversified across the globe—these questions loomed large over the work of long-range comparative linguistics in the late-1980s and early-1990s. Through newspaper reports, public television programming, and interdisciplinary appropriations, they were formulated at the intersection of specialist and general concerns. Publicity was actively pursued by committed “long-rangers,” who found themselves marginalized in an academic world dominated by more circumspect goals.

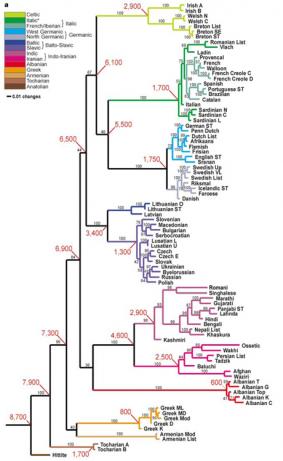

Figure 2: Map from Gray & Atkinson, “Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin,” Nature 426, p. 437. This was one of the first widely-publicized attempts to apply computational methods from evolutionary biology to historical linguistics.

Building on my doctoral research into the flowering of comparative-historical linguistics between 1874 and 1918, I analyze these developments in my project, Big Data and the Reconstruction of Linguistic Prehistory. The project pays careful attention to the political, cultural, philosophical, and methodological stakes involved in deep linguistic reconstruction. With respect to politics and culture, for instance, I explore potential correlations between references to linguistic monogenesis and the ‘un-freezing’ of the Cold War. Philosophically and methodologically, I show that the controversies surrounding proposed macro-families (for example “Nostratic,” “Amerind,” and even “proto-World”) have prompted historical linguists to reassess the foundations of their scientific practice (Figure 1). What constitutes the “cutting edge” in (pre)historical linguistics?—does progress mean tackling bigger mysteries or specifying existing models with greater precision? Are there limits to what linguists can know scientifically?—can the Comparative Method yield trustworthy results at any time depth, or does the swift rate of language change at some point render it useless? Long-range interventions have further sparked debate on the nature of data and the relative merits of quantitative versus qualitative methods. These debates are beginning to win support for the incorporation of interdisciplinary data-intensive practices, as reflected in journal publications and graduate training (Figure 2).

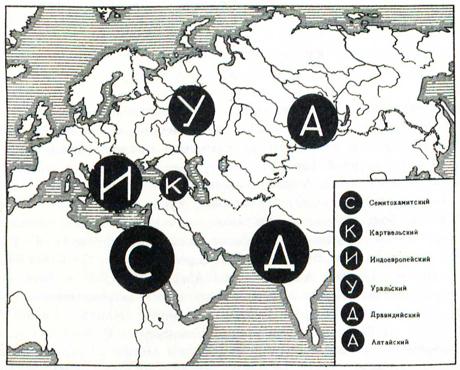

This project seeks to historicize a flurry of contemporary data-driven activities in the study of linguistic prehistory, exemplified by projects such as the Evolution of Human Languages database of the Santa Fe Institute and the Automated Similarity Judgment Program of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. It traces these back to late nineteenth-century efforts to generalize the methods of comparative-historical linguistics from the Indo-European family to other families world-wide. It then considers the origins of “lexicostatistics” in American linguistic anthropology of the 1950s and 1960s—presented as a critical emendation to earlier comparative work. From there, it describes the development of an inclusive Nostratic phylogeny—linking Indo-European, Altaic, Uralic, and Kartvelian languages in a very broad genetic grouping—among members of the “Moscow School,” which coalesced around the work of V. M. Illich-Svitych in the mid-1960s (Figure 3). Moving to the North American context, it recounts the controversies surrounding Joseph Greenberg’s classificatory overhaul of African and American languages using the method of “mass-” or “multilateral comparison”—a pencil-and-paper kind of Big Data approach. The survey concludes in the mid-1980s, when qualitative Soviet and quantitative American traditions began to converge. This collaboration was forged against the backdrop of heightened public curiosity in the sciences of human origins sparked by the announcement of the “Out of Africa” theory.

Figure 3: Map from the first volume of V. M. Illich-Svitych’s Dictionary of Nostratic (1971), p. 45. It motivated subsequent activities of the “Moscow School” and is one of the first sustained works of macro-comparative linguistics.

Big Data and the Reconstruction of Linguistic Prehistory contends that controversies engendered by long-range linguistic reconstruction can tell historians a great deal about tacit standards of evidence and method in the language sciences. More broadly, the project sheds new light on the collection, comparison, and classification of Big Data over the last 150 years.