In October 1711, Elizabeth Freke, an elderly gentlewoman living in rural Norfolk, compiled a list of “some of the best things” in her house. Freke’s room-by-room inventory, written into the notebook containing her memoirs and culinary and medical recipes, took four days to complete and records all of Freke’s worldly possessions ranging from jewelry and clothing to furniture and linens to pots and pans in the kitchen. In the midst of this detailed list, we find out that Freke kept, in her own closet, in five locked cupboards containing “several bottles of cordiall water 114 quarts; of pintts of cordy water 36. And of the severall sorts of sirrups is 56 quarts and pints.” Elsewhere, Freke reveals that in addition to these 200 bottles, she also owned extensive distilling equipment for making medicaments and a number of vernacular medical books. Medicine production was clearly a key activity in the Freke household.

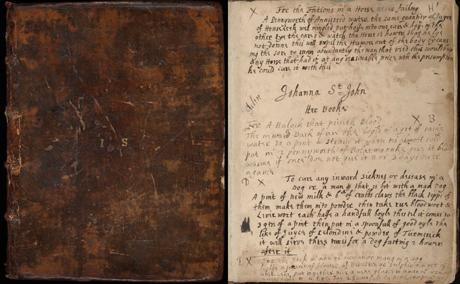

A few years before Freke compiled her inventory, another elderly gentlewoman, Lady Johanna St. John, sat down to write her will. St. John’s will contains the usual list of personal bequests—she left her bible to her eldest son, various pieces of furniture, paintings and silver to her daughters and granddaughters and small gifts of cash and linens to old, loyal servants. Alongside these usual gifts is the mention of two recipe books. The first is a book of “receipts of cookery and preserves” left to her “granddaughter Soame” and the second, gifted to her daughter Cholmondley was her “great receipt book.” The latter, now in the Wellcome Library, is a small leather-bound notebook with the initials I.S. embossed on the cover. Compiled over Johanna’s lifetime, the alphabetically organized book is filled with medical remedies addressing all sorts of ailments and sicknesses from agues to coughs to fevers. The listing of these two notebooks in St. John’s will suggests that collections of recipes, whether it was filled with instructions to make cakes or jams or medicines, were considered family heirlooms. In the same way that Elizabeth Freke considered her 200 bottles of medicines worthy enough to be locked up and included in her list of “best things,” Johanna St. John considered her own gathered household knowledge, in the form of her two receipt books, to rank amongst her most treasured possessions.

Fig. 2: Wellcome Library Western Manuscript 4338. Front cover and fol. 1r.

The import that these two elderly women attached to medicines and medical knowledge point to the central role which healthcare and medicine played within early modern homes. It also hints at the intense interest which medical and culinary recipes held for householders. Yet recipe collecting was not exclusively a female pastime, early modern fathers, uncles and sons were also keen participators in such activities. For example, in the 1650s, Edward Viscount Conway and Colonel Edward Harley exchanged and discussed recipes in letters and Sir Peter Temple created bespoke recipe books for his daughter Eleanor. While there is no doubt that collecting, exchanging and experimenting with recipes was commonplace in early modern England, with their dense listing of recipe after recipe with little or no theoretical explanation, many recipe books remain a puzzle to modern historians and literary scholars. Why were early modern men and women so curious and enthusiastic about recipes? What role did these texts play in creating home-based natural knowledge? How do recipes and practical knowledge fit into wider medical and scientific activities?

Household recipe collections, as compendia of practical know-how, constitute the crucial source for the study of informal knowledge-making. Compilers of such texts embarked on their journey by first seeking out and gathering new and pertinent information. Approaching friends, family and medical practitioners, they recorded the eagerly collected recipes into notebooks of various sizes. This information was then sifted, evaluated and modified by the household collective and only information which passed the test were adopted into the family repertoire. Thus, collections of recipes, though seemingly full of housewifery and domestic matters, are in fact records of a range of knowledge-making activities. Central to the recipe compilation process is first-hand experience and observation. Compilers assigned medical authority to possible recipe donors on account of their own experiences with or witnessing of particular cures. The testing and any subsequent modifications of the recipe were made based on actual first-hand trials conducted by family members and dependents. This emphasis on trial and testing was not intended to (and did not, for the most part) create new theoretical schemas; rather it was designed to determine and ensure the efficacy and reliability of individual remedies. Recent studies in history of science and medicine have challenged traditional concepts, sites and actors involved in the making of knowledge. Scholars such as Deborah Harkness have identified the early modern household, not only as a social, economical, political and intellectual hub but also as one of the main locations for a range of knowledge production activities. Concurrently, building on the call for a more inclusive definition of medical and “scientific” knowledge, Pamela Smith and others have pointed out the myriad of processes through which knowledge can be created: processes such as reading and writing, collecting of information and manufacturing of material objects (particularly connected with artisanal crafts and engineering). Building on past studies, Treasuries for Health further elucidates home-based medical and “scientific” activities and relocates these informal knowledge-making practices within overarching narratives of early modern medicine and science.

Fig. 3: A woman hard at work distilling. Scene opposite title page of The accomplished ladies rich closet of rarities (London, 1691). Image courtesy of Wellcome Library, London.

The gathering together of medical information in the form of short, concise recipes has a long tradition stretching from the ancient period to the late nineteenth century. While early modern English recipe collections are very much part of this tradition, they are particularly interesting as they lie at the confluence of several major shifts in the history of medicine and science and in the history of the book. Firstly, these books are created during a period when female medical care-givers working within domestic settings increasingly gained the necessary literacy skills to record and document their activities. Monica Green has recently argued in Making Women’s Medicine Masculine that as literate medicine gradually closed its doors to women in the Renaissance, the household recipe book opened to women as contributors, authors, experts and authorities. Analysis of these texts thus provides us with a unique glimpse into the sorts of knowledge early modern mothers, wives and daughters might have sought out, experimented and used and into the gender dynamics of knowledge production and transfer. Secondly, these books also detail the interaction of home-based and commercially available medical practices during a crucial period in the narrative of the commercialization of medicine and rise in the consumption of medical services. Finally, these books, flourishing in both manuscript and print, were also created in an age when the scribes, printers and readers worked to define the roles of the two communication media. Consequently, studies of recipes and recipe collections make for an ideal case study in the “search for order” not only in the field of the history of the book, but also in the fields of the history of medicine, science and gender.

Fig. 4: Anonymous, Portrait of Johanna St. John circa 1690, Collection of Lydiard House and Park. Image courtesy of Lydiard House and Park, Swindon.

Treasuries for Health is situated within the research framework set out in the Max Planck Society funded Minerva Research Group Reading and Writing Nature in Early Modern Europe. It is conducted in parallel with a number of cognate projects. The theme of notebooks, paper tools and paper technologies will be further explored in the 2013 workshop Notebooks, Medicine and the Sciences in Early Modern Europe organized with Lauren Kassell at the University of Cambridge. In 2014, in collaboration with Alisha Rankin at the Tufts University, the MPIWG will host the working group Testing Drugs and Trying Cures in the Early Modern World, which aims to investigate issues of trials, experimentation and assessment of pre-modern cures. Finally, in collaboration with Lisa Smith at the University of Saskatchewan, I run “The Recipes Project,” an online resource creating crowd-sourced transcriptions of early modern recipe texts and an academic blog bringing histories of pre-modern recipes to general audiences.